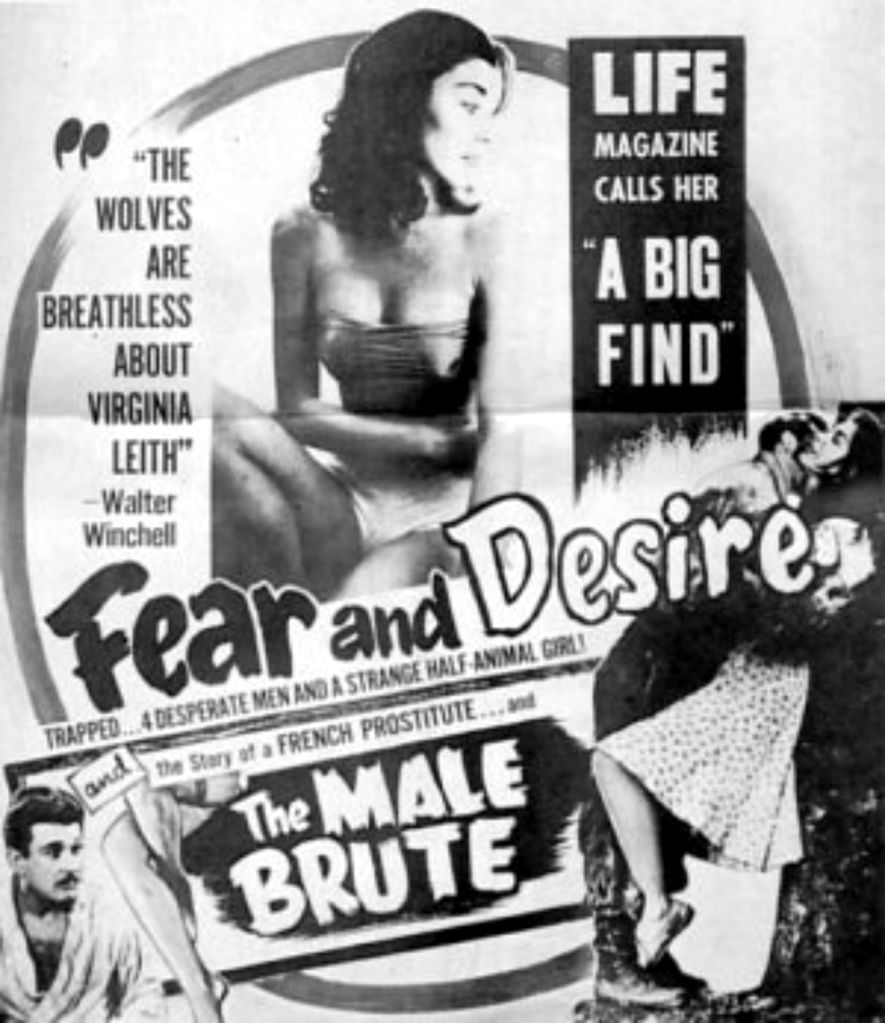

The local cinémathèque-cum-art-cinema prepared a retrospective of Stanley Kubrick’s films. The only omitted one was his directorial debut, Fear and Desire (hence the title of this blog entry)[1].

Kubrick was not a prolific director, he made only 13 feature films in 46 years. That means 0.28 films per year, that is 3.54 years per film[2]. Some of his unrealised projects are even more famous than some he actually managed to bring to fruition, Napoleon being the most well-known of them.

Unfortunately, as was the case with 小津 安二郎 (Ozu Yasujirō) and אפרים קישון (Ephraim Kishon), the cinema stuck to its policy of showing two films back to back on the same day if they last less than 2 hours each. Viewing two films by a great director in the same night means not being able to absorb each of them satisfactorily.

Luckily most of Kubrick’s (screened) films are longer, only Full Metal Jacket (1987), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956) and Killer’s Kiss (1955) do not reach the 120 minutes mark.

There is a thing about Kubrick. Or, more precisely, there is not. With Jacques Tati you know that you will watch a minutely choreographed visual comedy. With 小津 安二郎 (Ozu Yasujirō) you know that you will watch a comedy-ish story of interpersonal relationships within a contemporary Japanese family. With Kubrick you do not know. Kubrick is known for never returning to an already explored genre. The only exception to this rule might be the pair Paths of Glory ‒ Full Metal Jacket under provision that both are labelled as anti-war films[3].

Of course that the programme began with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the most celebrated of his works. It also best represents some of Kubrick’s stylistic features, the famous tracking shots (not so much the Kubrick look), but also the choice of music. In some movies that choice was dictated by the story itself (e.g. A Clockwork Orange), but here it is somehow the other way round. Kubrick popularised some classical music by incorporating it perfectly in appropriate sequences. Just to remind you, the music used is Արամ Խաչատրյան’s (Aram Khachaturian) Adagio from his ballet Գայանե (Gayane) (introducing Bowman and Poole aboard the Discovery), three pieces by Ligeti György, Kyrie from Requiem for soprano, mezzo-soprano, two mixed choirs and orchestra (the monolith’s encounter with apes, the monolith’s discovery on the Moon and Bowman’s approach to it around Jupiter just before he enters the Star Gate), Lux Aeterna and Atmosphères (Bowman actually enters the Star Gate), Johann Strauss II’s An der schönen blauen Donau and Richard Strauss’s introduction to Also sprach Zarathustra as the main leitmotiv.

The interesting aspect of this film, not present in his other “big” films, is rather unknown actors being cast[4], Keir Dullea as Dr. David Bowman, Gary Lockwood as Dr. Frank Poole, William Sylvester as Dr. Heywood Floyd and Douglas Rain as the voice of HAL 9000. I do not say that they did no big (and small) screen acting before 2001, just that neither of them ever became a big star before 1968. Kubrick probably did not want this film to be burdened with stars (got it?) and even less with excessive dialogue, most of it is told though images and music. A friend of mine, who was a great fan of the film when it first appeared, smuggled a cassette recorder into the cinema and recorded the sound of the whole film. By listening that recording I became aware how little is said during its 142 minutes! Fun fact: If you remember Bowman’s last words “Oh my God ‒ it’s full of stars!” they never appear in the film. It is just a Mandela effect[5]. The first time they are actually heard is in the film’s inferior sequel, Peter Hyams’s 1984 film 2010: The Year We Make Contact[6]. Another quote that actually is in the movie is Frank Poole’s (talking about HAL 9000) “I’ve got a bad feeling about him,” nine years before Han Solo & Co. made “I have a bad feeling about this” a worldwide-known catchphrase. Another line of dialogue, HAL’s “Dave, I’m afraid” reminded my (do not ask why and how) of Holly’s “Everybody’s dead, Dave” from Red Dwarf.

One Robert B. Frederick, who allegedly earns for a living by acting as a “film critic” for Variety, wrote in 1968: “… a group of apes (the makeup is amateurish compared to that in Planet of the Apes).” Did he actually think that those obvious humans in Halloween ape suits are more convincing than our distant ancestors as depicted in 2001? Or was he just sight impaired?

Anyway, 2001 aged well, much better than Planet of the Apes or any SF from those days. Its technology looks top-notch (or what will be top-notch in the future) today as it did then. Maybe it would be more correct to say that it did not age at all at all.

One thing that only Kubrick seemed to get correct in space movies is the silence in space. There are no wooooshes, pew-pews, booms and other sounds out there. No sound in vacuum. Kubrick knew it. Other space opera directors did and do not.

Just one question: did tapirs live in Africa at the times of our distant ancestors? There is no evidence indicating that they ever existed in Africa, so it is likely they were probably added simply for their “prehistoric” appearance. In the novel, they are replaced by warthogs.

And to conclude, if you have not read it yet, I warmly recommend Arthur C. Clarke’s half-fiction book The Lost Worlds of 2001 in which he chronicles the naissance of 2001. I believe that it is in there that it is said that the screenplay should be credited to Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke after the novel by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick, and that the novel should be credited to Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick after the screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke.

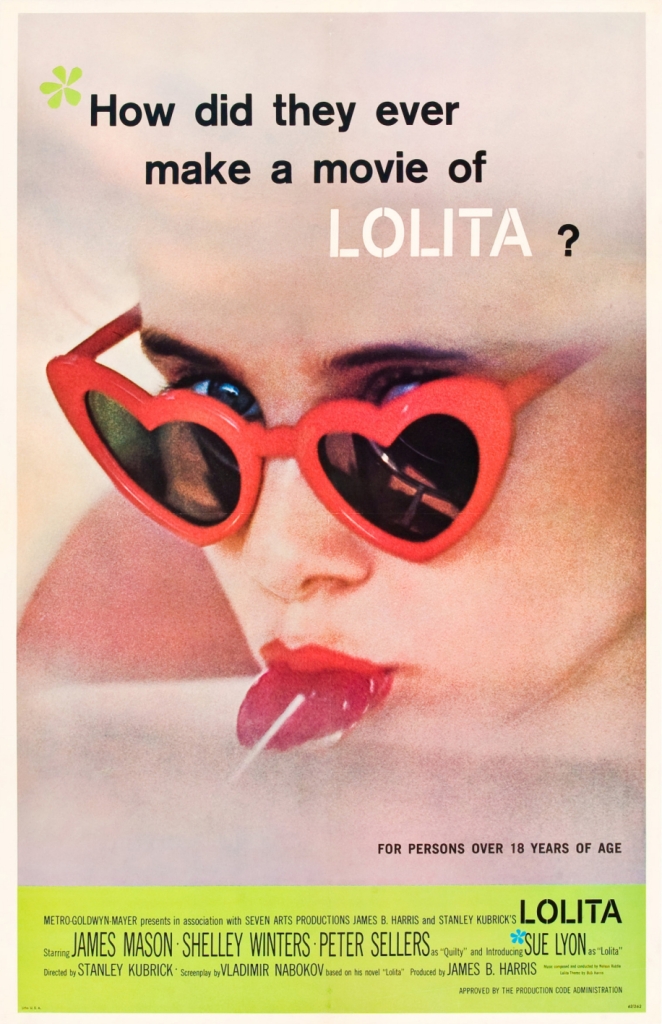

I read Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita a long time ago, when I borrowed the book from my then girlfriend. I liked it a lot, it was both funny and tragic. I am still wondering how normal those times were before some very uncouth and uneducated and uncivilised individuals started imposing their Iron Age morality on the civilised world. I saw Kubrick’s film version (1962) much later. This is a more typical case in Kubrick’s filmography than 2001. Of all his films only Fear and Desire, Killer’s Kiss and 2001 are not based on previously published material.

However, even in 1962, owing to restrictions imposed by the outdated thirty-two-year ancient Motion Picture Production Code as well as the Catholic Legion of Decency[7], the film was forced to tone down the most provocative aspects of the novel, sometimes leaving (too?) much to the audience’s imagination. So, what did happen between Humbert and Lolita? Kissing? Petting? Intercourse? Even then, and even more today, prohibitions of that kind cannot be regarded upon otherwise but as as primitive, backwards and stupid as the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC)[8] or as any SJWankers of today.

The problem of false moralists treating any children in art as pure paedophilia is denounced by a brave internet site that proclaims that such views can only be held by closeted paedophiles.

So Lolita herself has been adulted a little, from twelve (as in the book) to fourteen (in the film), the age of Sue Lyon while playing the title role[9].

The casting is superb, James Mason is a convincing extrovertly emotionally repressed, but internally boiling Humbert Humbert. Shelley Winters, one of the great USA so-called “character” actors[10], who alas! never conformed to Hollywood’s narrow concept of what a film star should look like[11], is the perfect love and sex hungry Charlotte Haze, never crossing the line to become a mere caricature. Sue Lyon is perfect in the title role of self-conscious minor sexual extorter. And Peter Sellers shines in the role of Clare Quilty that enables him to demonstrate some of his chameleonic abilities[12].

An important part of the film is that there is not a single positive “good guy” character among the leading quartet. Not even Lolita, who is a shrewd manipulator of all the men around her. She is well aware of what she possesses that makes men jump to her command. And she uses it relentlessly and profoundly. The film leaves no doubt that she pays favours with her looks, and her body too. She is far from being an innocent adolescent. More a scheming gold-digger.

Fun fact: the recurring dance number first heard on the radio when Humbert meets Lolita in the garden later became a hit single under the name Lolita Ya Ya with Sue Lyon credited with the singing on the single version.

Thirty-five years after Kubrick, Adrian Lyne adapted Lolita for the big screen once more. However, the casting was not as strong as Kubrick’s. Another British actor, Jeremy Irons, subscribed to roles of wretched intellectual losers, replaced Mason. Seventeen-year old Dominique Swain playing a fourteen-year old replaced Lyon. Melanie Griffith replaced Winters. And finally, Frank Langella replaced Sellers. If we can talk of proper replacements here. Neither Griffith nor Langella can match Winters’s and Sellers’s acting talents and performances, so overwhelmingly important in the whole of Kubrick’s Lolita.

The next couple of films were the first to be screened the same evening. Which is very interesting, because they represent two aspects of war. One is about war of machines against people, dealt much more realistically with than in the Terminator franchise. The other is about war of people against people, not of enemies against enemies, but of soldiers against their own soldiers[13].

“Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here. This is the War Room!” and Peter Sellers in his triple role of group captain Lionel Mandrake, president Merkin Muffley and former Nazi nuclear war expert Dr. Strangelove. OK, now that we have dealt with the essentials, we can continue to the film.

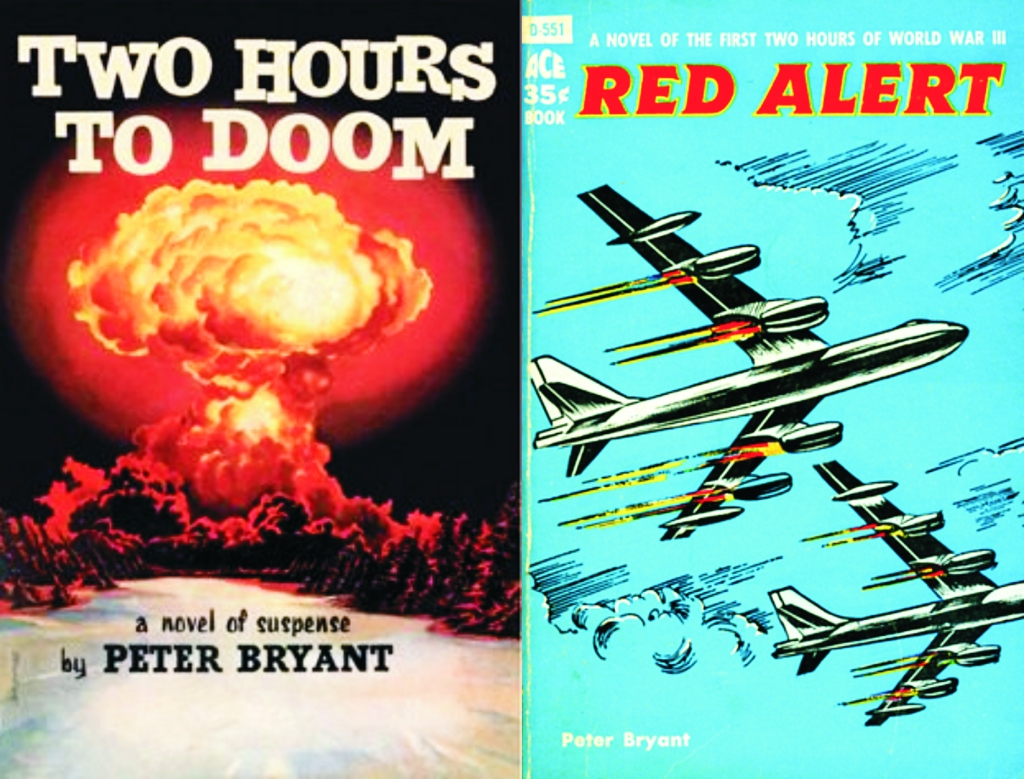

The film’s full title is Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), which is much longer that the title of the book that inspired it: Peter George’s Red Alert (1958), originally published under the title Two Hours to Doom and under the nom de plume Peter Bryant. The key word here is “inspired”, because it depicts precisely what Kubrick did with his written sources. He did not adapt them so much to the big screen as adapt them primarily to himself. He turned every one of those sources into pure Kubrick. And this film is the best example. Red Alert is a thriller, Kubrick’s film is a black political satire.

The firm satirises the typical USA claustrophobic paranoia, inaugurated by General Dwight Eisenhower in the 1950s, when he ascended to the Oval Office. (Which is a practical demonstration why generals, a paranoid brood in itself, should never be allowed to occupy positions with great responsibility.) The tragedy of the present time is that that same chronic paranoia is now being disseminated by USA to its overseas colonies, protectorates and other dependent territories, along with its outdated iron-age wannabe-morality.

Besides Sellers, three other actors have presented memorable over-the-top roles in this film. Among the most memorable ones of their careers.

The role of B-52 pilot Major T. J. “King” Kong was initially intended for Sellers as well. However he had an injury that prevented him from doing it, but some say that he was not quite comfortable with a cowboy role. Anyway, I can only imagine Slim Pickens, a rodeo rider and minor western actor, coming to the audition in his cowboy boots, ten gallon hat and Texas drawl. It must have been love at first sight. It is notorious that Kubrick never let the actor read the whole script, but only the B-52 pages of it, leaving him convinced that he is acting in a serious war film. And Pickens did it. And created one of the greatest comedy roles in film history. As film critic Roger Ebert put it: “People trying to be funny are never as funny as people trying to be serious and failing. … A man wearing a funny hat is not funny. But a man who doesn’t know he’s wearing a funny hat… ah, now you’ve got something.” Alas, many contemporary comedians and “comedians” do not understand this. But let us go back to Pickens. He credited Dr. Strangelove as a turning point in his career. Previously he had been “Hey you” on sets, and afterward he was addressed as “Mr. Pickens”. He once said, “After Dr. Strangelove, the roles, the dressing rooms, and the checks all started gettin’ bigger.”

The second great role is that of General Buck Turgidson played majestically by the great George C. Scott, making it one of two memorable roles of his career (the other is of course 1970’s Patton). Kubrick used a diametrically different tactics with Scott. He urged him to act the scenes over-the-top just for practice before the real ones were filmed, and then used the former in the film. What we got is a rich ballet of his face muscles and body postures. He makes funny faces but not for funny faces sake, like say Jim Carey or Rik Mayal, but to convincingly portray a general proud of his boys who are so able to evade all Soviet anti-aircraft defence and bring an end to humanity and civilisation.

The third memorable role is that of Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper played maniacally by Sterling Hayden. I do not know what Kubrick did to him to obtain the scary deranged paranoid lunatic Hayden so faithfully portrayed in the film.

So Peter Sellers famously played three different roles in the film, yes? However, this still does not beat his Ladykillers colleague Alec Guinness, who in Robert Hammer’s 1949 black comedy Kind Hearts and Coronets played nine members of the D’Ascoyne family: the late 7th Duke of Chalfont in brief flashback sequences, his children, Ethelred, 8th Duke of Chalfont, the Reverend Lord Henry, General Lord Rufus, Admiral Lord Horatio, the banker Lord Ascoyne and Lady Agatha D’Ascoyne, as well as his two grandsons, Young Ascoyne and Young Henry.

Should I mention the hilarious names given to the characters? Like Bat Guano, Buck Turgidson, de Sadeski, Jack D. Ripper, “King” Kong, Kissoff, Lothar Zogg, Mandrake, Merkin Muffley?

The film is so drenched in sex that I am surprised that it was not banned forever in USA. It starts with two airplanes copulating in mid-air (look how that fuelling rod wobbles in and out!), General Ripper is obsessed with his bodily fluids and constantly munches a penis-like cigar, and General Turgidson is very interested in the 10 to 1 ratio of women vs. men in the nuclear shelter.

In his 1982 autobiography Mon Dernier soupir, Luis Buñuel mentioned Paths of Glory (1957) as one of his favourite films. And that means something!

Kubrick set Dr. Strangelove in three locations, the Burpelson air base (interior and exterior), the B-52 and the War Room. In this film he used three different locations to illustrate the difference of living conditions of ordinary soldiers and their immediate superior on one side and the generals on the other.

The trenches are bleak, muddy, dirty, cold, wet. And the officers’ quarters are just slightly better. On the other hand there is the château, where the generals reside. The interiors of the château, played by the Bavarian Schloß Schleißheim, the summer residence of the Bavarian rulers of the House of Wittelsbach, are so bright and clean that they look like overexposed shots. The stretching of the trenches gave Kubrick the opportunity to engage in his signature tracking shots. In the château, where there are no such restrictions, the camera plays a waltz with the actors, moving around them and the furniture and the columns in vast rooms.

The other contrast between Colonel Dax, the commander of the troops in trenches, and the generals well hidden in the château is that he is the leader of his men, he is the first to leave the trenches and goes in front of his men during the ill-fated attack, while the latter are cowardly hiding far behind the front to watch what is going on through powerful binoculars.

Dax is artfully played by Kirk Douglas, the first great Hollywood star to star in a Kubrick film, and the man who made the adaptation of Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel possible through his own production company. He asserted that Kubrick was a difficult director to work with, demanding innumerable retakes, but in a 1969 interview he said about the film: “There’s a picture that will always be good, years from now. I don’t have to wait 50 years to know that; I know it now.”

The whole court-marshal scene depicts it at it is: a farce. The men were condemned the moment they were accused. The proceedings have a lot in common not only with medieval and post-medieval witch-hunts, including those by the disreputable Joseph McCarthy, but also of many proceedings of today[14].

The film ends with one of the strongest and most memorable sequences in film history. A frightened captured German girl is brought before French soldiers to entertain them. By singing a simple folk song, Der treue Husar, she manages to calm a pack of howling Tex Avery wolves into snivelling little boys overwhelmed with nostalgia and homesickness.

That single scene demonstrates how much understanding there is between ordinary people on both sides of the barbed wire and how great is the divide between the ones on the top and the ones in the bottom on the same side of the barbed wire. Jean Renoir’s 1937 masterpiece La Grande Illusion tells of the same divide. German and captured French officers socialise, but ordinary French soldiers, fugitives from the POW camp come to understanding with a German woman whose language they do not speak.

Paths of Glory is based loosely on the true story of the Souain corporals affair, when four French soldiers, clockmaker Louis Victor François Girard, married with one child, waiter Lucien Auguste Pierre Raphaël Lechat, single, railway worker Louis Albert Lefoulon, living with a partner with one child, and town hall employee Théophile Maupas, married with two children, were being murdered in 1915, during World War I by orders of General Géraud Réveilhac[15] for failure to follow orders. The soldiers were exonerated posthumously, in 1934. Needless to say that the soldiers themselves did not give a damn for the exoneration.

The morale of the film is pretty clear. The greatest enemy of a soldier in a war is not the enemy, it is his superiors. Or, as film critic Mike Lorefice puts it: “One way or another, we all realize that the greatest military leaders are also the greatest murderers of their time”.

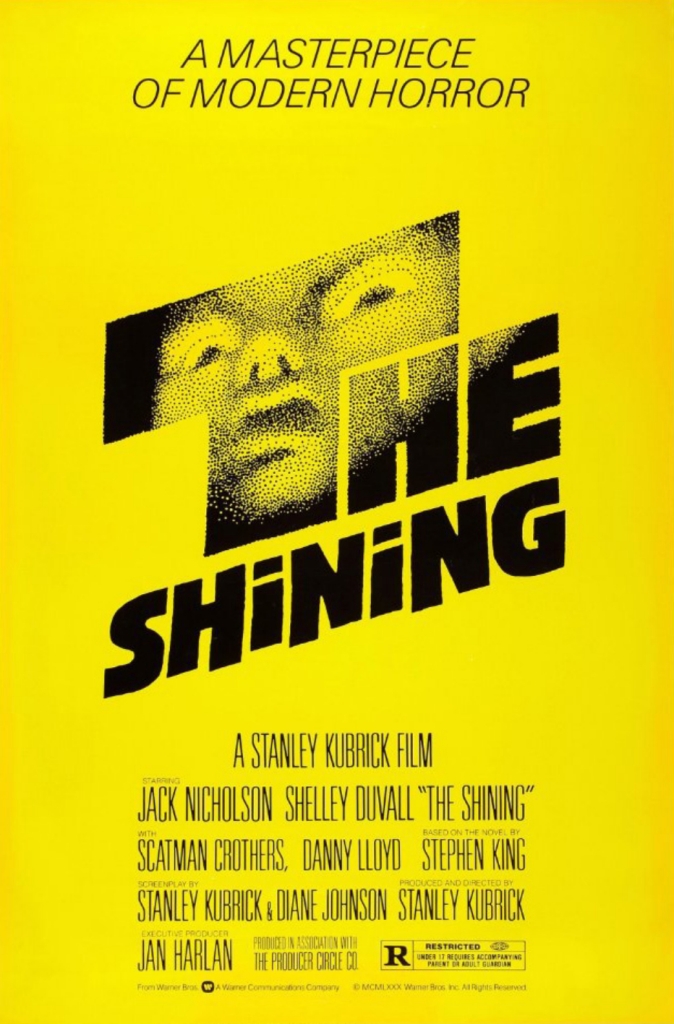

There are two types of Stephen King film adaptations: the ones he did not make and is deeply unsatisfied with them and the bad ones. There are also two types of horror films: the ones in which someone for no reason kills other people and the ones in which the horror sensation comes from inside[16].

The Shining (1980) belongs to the first ones among the former and the last ones among the latter.

The film is set in a typical horror environment, an isolated spot to which no help can come and from which it is not easy to escape to security. But this is the only concession made to the stereotypes of the genre. Film critic Lee Lescaze called it “a thinking-man’s horror film”, while film critic Bruce McCabe summarised it: “It’s a horror story even for people who don’t like horror stories ‒ maybe especially for them[17].”

So, if you are a fan of predictable horror stuff, this is most definitely not a film for you. There are no Freddies Krugers, Michaels Myerses, Jasons Voorheeses or Xenomorphs. There are just daddy Jack, a questionably recovered alcoholic and family bully, his powerless wife Wendy and their (psychic?) son Danny with his invisible friend Tony.

Is it the cabin fever that drove them crazy? And who exactly of them is going crazy? Only Jack? What about Danny and his visions? And what about Wendy? And what is it exactly that drives him/her/them crazy? In fact, the uncertainty remains: what of it all is true and what is not?

Luckily, Kubrick does not bother to give rational explanations. And that is a good thing. Allegedly, there was an explanatory scene but it was fortuitously cut off from the film’s end. Good riddance!

It is often noted that whenever Jack sees ghosts there is a mirror present (behind the bar, in the toilet,…), suggesting that whom he sees and with whom se talks is his reflection. Again, if that explanation satisfies you, it is OK. I rather leave the ending open to myself and everybody else who is able to accept it like that.

Shelley Duvall’s revelation of her difficult experience with Kubrick and this film has also become notorious. Was Kubrick the only ghost that turned them all crazy during the shooting?

Here is another film that uses classical music to enhance the visuals. Wendy Carlos (who vowed never to work with Kubrick again) and Rachel Elkind preformed Hector Berlioz’s Dies Irae from Symphonie fantastique: Épisode de la vie d’un artiste … en cinq parties, op. 14. There are also pieces by notable 20th century composers, Bartók Béla’s Zene húros hangszerekre, ütőkre és cselesztára (Sz. 106, BB 114) (Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta), Ligeti György’s Lontano and Krzysztof Penderecki’s Ewangelia and Kanon Paschy from Utrenja, Przebudzenie Jakuba, De natura sonoris no. 1 and 2, Canon and Polymorphia. As well as some pop recordings during the ballroom scenes.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999) is not only the last but also one of the longest films Kubrick ever made. Bad news for weak bladders! The cinema was a veritable promenade to and from the toilets.

Another adaptation, or should I say Kubrickisation, this time of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 Traumnovelle set in early-20th-century Vienna during Fasching. Eyes Wide Shut is set in New York City in 1999 during the Christmas season.

The film examines sex in society. To be more precise, its dehumanisation. Dehumanisation is a constant theme in Kubrick’s filmography (Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove, 2001, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket), but here it pierces into the most personal and private zone of human beings. Sex, as depicted in the film, is impersonal. As film critic MaryAnn Johanson put it: “Kubrick isn’t just divorcing sex from love ‒ he’s divorcing sex from lust.” The mathematic is easy: no intimacy = neither love nor lust.

The married life of the Halfords seems to be all foreplay, no copulation. Not even some heavy petting. They seem to avoid it. Alice is having strong imagined and dreamt sex with multitude of men. And Bill is interrupted every time that some sex is overtly or covertly proposed to him. Even if he were not so rudely interrupted, I doubt that he would engage in it, I am pretty sure that he would avoid it all the same.

At Ziegler’s Christmas party, two models try desperately to drag him to bed, but Ziegler’s emergency call interrupts them.

Marion, his deceased patient’s daughter, hits heavily on him in the room where her father’s body lies, he resists (for how long could he?), but the arrival of her fiancée interrupts them.

Domino, a prostitute, invites him to her place to have some fun, he goes, but he avoids it.

Milich, the costume shop owner, pimps his underage daughter to him, he avoids it.

The clerk at his friend’s hotel, an obvious homosexual, hits on him, he avoids it.

Sally, Domino’s flatmate, also hits on him, he avoids it.

Bill turns out to be not so much an agens[18] as a patiens[19] in all these more or less open flirtations. The question remains why. Why it never comes to carnal consumption? Because he is faithful to his wife, marriage, daughter et al.? (It is interesting to note here that it is the male of the couple that wants commitment, while the woman fantasises about non-committing casual sex!)

Hardly so, he is constantly persecuted by the black-and-white image of his wife being sexually satisfied by an anonymous soldier whom she saw when they were vacationing at Cape Cod and felt an instant desire to surrender her body and her life to him. Considering marriage as a property relation (his wife! mother of his daughter!), just as prescribed by the Bible, he obviously wants some kind of retaliation for a misdeed that was never done, except in her mind, but seems unable to do it himself. Her adultery never actually happened, it was just wished for and imagined by her. This is a clear representation of the caricatured system in which thoughtcrime is not just a word coined by George Orwell anymore. If people would be actually judged for their thoughts, a great part of humanity would be incarcerated as murderers, robbers, sex maniacs, rapists, child molesters or ombudsmen.

The dehumanisation of sex conquers its peak in the orgy scene. Everybody is wearing masks. The masks dispose no intimacy at all. The masks impede sex partners to watch each other, to enjoy the sight of a face not hiding bodily satisfaction, the masks prevent sex partners from kissing, that most intimate touch during sex. Masks become a necessity in a society where some “incorrect” sex, sex not condoned by the social order, is a greater crime than mass murder.

Unfortunately, the orgy scene was molested by the production company in its yearning for a rating that would provide a more profitable sale of pop-corn, allegedly with Kubrick’s consent. As film critic Roger Ebert, comparing the result with Austin Powers, wrote: “With or without those digital effects, it is inappropriate for younger viewers. It’s symbolic of the moral hypocrisy of the rating system that it would force a great director to compromise his vision, while by the same process making his adult film more accessible to young viewers.”

As in some other films by Kubrick, we are transported into a different reality. To quote film critic James Berardinelli: “In Dr. Strangelove, it was a world where the Cold War had gone mad. In 2001, it was HAL’s domain. In A Clockwork Orange, it was an Orwellian future. In Full Metal Jacket, it was Vietnam. Here, it’s an underground realm of sex parties and orgies.”

The post-orgy part of the film follows Bill looking for answers. Eventually, he gets them from Ziegler. But did the events unfold the way Ziegler narrates them to Bill? Ziegler is one of the in-crowd, after all. The truth? We will never know it. But that is not the problem. We exit the cinema and do not have to live with it. Bill stays inside and has to.

The principal roles are played by the then dream team couple of Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise. The whole film lies on Bill as the main character. And here is the problem. Regardless of his later image of the action hero who does his own stunts, Tom Cruise is seldom something more than a pretty face. Yes, he did star in some good (or at least popular) movies, like Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money (1986), Barry Levinson’s Rain Man (1988), Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Rob Reiner’s A Few Good Men (1992), Sydney Pollack’s The Firm (1993), Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994) and Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire (1996), but I never got the impression that he ever advanced from his pretty face status[20]. The burden is too much for him to carry the whole film on his weak shoulders. Some scenes, and he is in almost all of them, work and some do not.

Nicole Kidman, on the contrary, is at her best. She already proved in several films what a good actress she is. Whenever she is on screen, things work out. She was pretty nervous about doing nude scenes, and Kubrick encouraged her to bring some music to the scenes to help her. Later he incorporated that music of her choice into the film. Maybe this is just in the eyes of the observer, but I would say that that uncomfortableness is exactly what makes her so sexy in the whole film.

The final dialogue perfectly summarises the whole idea of the film, the one stated above in the text: “The married life of the Halfords seems to be all foreplay, no copulation.” Alice informs Bill that there is one thing they simply must do before anything else. To his question what that should be, her answer is succinct: “Fuck.”

At this point it is needless to mention Kubrick’s masterful use of music. Not only the usual classical pieces, like Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович’s (Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich) Waltz N. 2 from Cюита для эстрадного оркестра в восьми частях (Suite for Variety Orchestra), Ligeti György’s second movement of the piano cycle Musica ricercata, Franz Liszt’s solo piano piece Nuages Gris, S.199, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Rex tremendae from Requiem.

But even more intriguing was the music assembled by the film’s composer Jocelyn Pook for the orgy ritual. The whole scene is deeply immersed in a dark mysticism and Pook came with the perfect solution to incorporate some mystic and sacred music in it. She took a Romanian Orthodox Divine Liturgy recorded in a church in Baia Mare and played it backwards. In another music for the orgy she included a Tamil song sung by மாணிக்கம் யோகேஸ்வரன் (Maanikkam Yogeswaran), a Carnatic singer, that replaced the originally intended scriptural recitation from the श्रीमद्भगवद्गीता (Śrīmadbhagavadgītā), after the South African Hindu Mahasabha group protested against the scripture being used.

The next two films were screened the same evening.

A Clockwork Orange (1971) has probably the best-known musical score of all Kubrick films with the possible exception of 2001. As Alex[21], the protagonist of the story, is a Ludwig van (as he himself puts it) buff, it is expected that Beethoven’s music must occupy a significant part of it. And it does. Two movements of his Ninth Symphony in D minor, Op. 125,[22] appear in generous portions, the second, Molto vivace, and the fourth, the choral Finale, now so sadly misused and abused as the “anthem” of the so-called “EU”. They appear in two versions each: orchestral and electronic, the latter bestowed by the then still Walter (her albums were signed by Wendy from 1980 onwards) Carlos[23]. Five more classical compositions accompany some scenes, two of them overtures by Gioachino Rossini, La gazza ladra and Guillaume Tell. You may remember the latter from chase scenes in classic golden-era cartoons. Two other are two of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance Military Marches, Op. 39, Nos. 1 in D and 4 in G. The last classical piece is the oldest of them all, Henry Purcell’s March from Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, Z. 860. It also appears in an orchestral and an electronic version and is now widely known as Title Music from A Clockwork Orange.

I read the book (translated) years before the film was shown in my city. And even then it was not in cinemas, but on TV. So I watched it for the first time knowing what it is all about.

What we see in that film is a not distant, if distant at all, future. A corrupt state, lead by a fascistoid and adequately corrupt government unable to furnish the population with normal living conditions because of being too occupied with incarcerating political prisoners. As we all know, in such a dictatorship a political prisoner is more dangerous than a criminal one. The reason for this is simple: you can corrupt a criminal to work for you, to do the same job as while being an outlaw, but paid for it[24]. The problem arises when the adversaries of such a government, candidates for the political prisoner status, are not fundamentally different from the ones in power. And those in power will make a full turn of their politics to both avoid criticism and gain more positive points. It is the classical “anti-corruption” politics in many institutions: they use corruption to their advantage and this is wrong. Elect us so that we can stop them and start using it to our advantage!

The government acts as the omniscient deity who does not give humans free will but takes it from them by the use of drugs and other suspicious methods. Interestingly enough, the prison chaplain is the only one protesting the Ludovico method, to which Alex would soon be subjected.

What we see in that film is more of a kitsch than a pop-art future. Alex’s mother is wearing some hilarious plastic clothing and footwear. The family’s living room’s wall is adorned by some inverted bowl ornaments. It seems that purple hair from UFO’s Moon Base has become all the rage, both Alex’s mother and the psychologist wear it. The architecture, on the other hand, is brutalistic. Concrete slabs scattered around, deserted as a Giorgio de Chirico painting. Not a future (or present, for all that matters) in which I would like to live.

All those who objected to Eyes Wide Shut for showing exclusively female full frontal nudity now have a chance to inspect Malcolm McDowell’s penis a while. I am not an expert when it comes to penises (I hope that some of you can help me with your evaluation in the comments), but it seemed rather alright to me.

The funniest scene occurs in the hospital when moans of a nurse having sex with a doctor and moans of Alex waking up from his coma echo each other. The image of the nurse and doctor rushing into the room, she with her tits loose and he with his trousers around his ankles is unforgettably hilarious.

This film represents one of the top triad of Kubrick’s opus, together with Dr. Strangelove, seven years its senior, and 2001, made three years before this film. What comes as a kind of surprise is the economic storytelling. Unlike some of his other films, this one does not assume some epic proportions but forwards the narrative in a swift and logical fashion from one sequence to the next.

The thing that is really worth seeing in A Clockwork Orange is Darth Vader in some sexy skin-tight short shorts!

Killer’s Kiss (1955) is the second feature film made by Stanley Kubrick. Written, directed, cinematographed and edited by Stanley Kubrick.

It is a film noir made after the genre’s heyday. The visual style of those films owes a lot to German expressionism and even more to the fact that many German filmmakers (including cameramen) have fled Hitler’s Nazis and moved to USA. It is a rather pessimistic genre, its stories usually being about losers, not with a happy ending.

Kubrick’s film follows faithfully the premises of the genre, except for the happy ending that was forced upon him by the producers. The claustrophobic feeling is evoked by the small enclosed boxes through which the characters have barely the space to move, the apartments, the office, the boxing hall, even the boxing ring. Contrasted to them are the big, open spaces through which the final chase is presented. Those shots make us lament Kubrick’s decision to leave the camerawork to someone else in his future films. His eye of an ex-professional photographer is visible in every cadre of that part of the film. The marvellous play of black and white brings to mind the best graphic pages drawn by comic strip masters like Will Eisner (Spirit, 1940‒1952) and Roy Crane (Buz Sawyer, 1943‒1979). The film includes a dream, more of a nightmare negative-image sequence of the camera racing through an endless, straight New York street that anticipates Bowman’s voyage through the Star Gate in 2001. Another stunning visual is seeing the boxing match from the point of view of one of the fighters. How much did Kubrick’s experience from his 1951 documentary short Day of the Fight (that I have never seen) affected and influenced the fight scene in Killer’s Kiss?

The story is told in layers, in a flashback that contains flashbacks. A surrealist scene of a dancing ballerina on a black background accompanies Gloria’s story of her (sister’s) life. Its mere disconnection with the scenes that precede and follow it stress the importance of Gloria’s explanation why and how did she end as a dance girl for hire within the main frame of the overall story.

And here we come to the main problem of the film. There is too much diegesis[25] in it, and not enough mimesis[26]. Too many things going on are described verbally instead of shown happening. This is something that Kubrick was going to jettison soon in his future career, which will make his films longer and visually attractive.

The sequence of the final fight between Davey, the good guy, and Rapallo, the bad guy, the former armed with a pike, the latter with an axe, in a mannequin storeroom is the second visual culmination of the film (the first was the chase scene that preceded it, remember?). Camera cutting from the fight itself to decapitated heads and hanging arms as well as the fighters hitting each other with body parts makes this sequence even more surrealistic than the ballerina one. It is one of the great fight scenes ever filmed and I cannot believe that it was not carefully choreographed[27].

The derelict New York streets, apartments, offices,… evoke Italian neorealism, the camerawork and lighting (even in this early film Kubrick showed his penchant for using lights available in the set) German expressionism and the ballerina and fight scenes French surrealism. Kubrick has managed to offer a nice visual mixture of genres incorporating it in a visual unity of his own camera.

I wrote before that there is a happy ending forced upon the film. There is still a shadow of a doubt: when Gloria was badmouthing Davey in front of Rapallo and his henchmen, was she lying to save Davey’s life of was she sincere? Davey no doubt heard it. Can he be sure that her feelings for him are real, or is she just using the winner of the battle that two men fought for her as a mere means to get the hell out of there?

I must admit that Irene Kane is very cute and I am sorry that there are virtually no other films in which I can watch her[28].

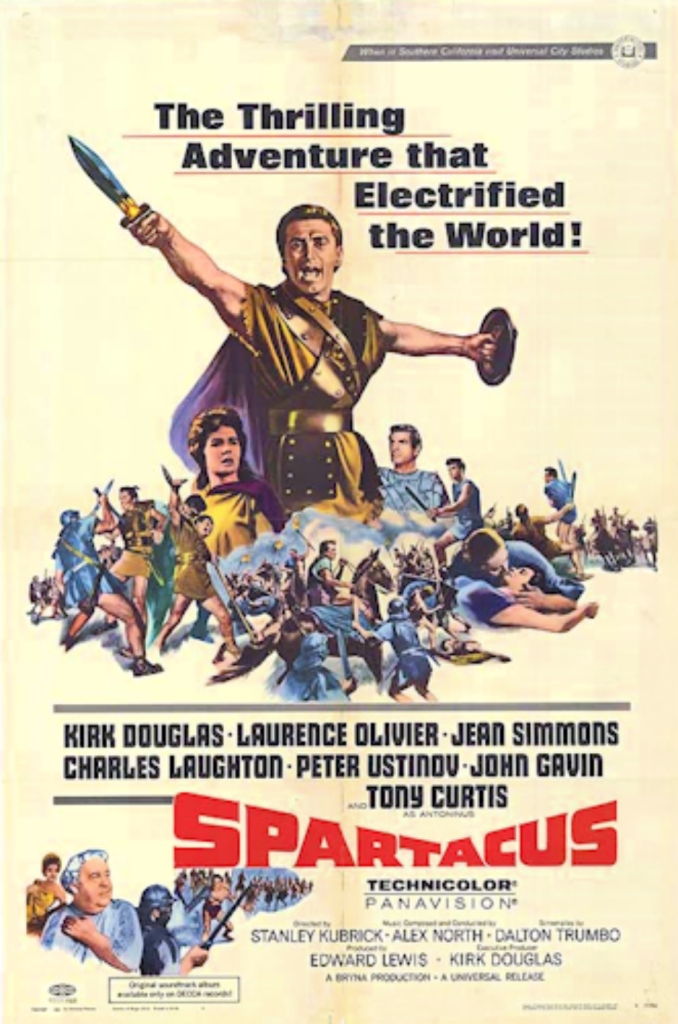

Is Spartacus (1960) a Stanley Kubrick film? Well, he did direct it. However, this is his only film over which he had not complete control.

The one who had control was Kirk Douglas, the star playing the titular role.

It is notorious that Kubrick used some actors for minor roles in several of his movies repeatedly, but he rarely engaged the same actor for some of the big ones. There are three exceptions. Sterling Hayden played the leading role in The Killing and the maniacal cigar-munching General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. Peter Sellers played Clare Quilty in Lolita and the three famous roles in Dr. Strangelove. Finally, Kirk Douglas played the leading role in both Paths of Glory and Spartacus.

The story of how the film came to be is well-known. Disappointed that the leading part in William Wyler’s 1959 Ben-Hur was given to whining, whimpering and puling Charlton Heston instead of him, he searched for some other similar project in which he could star. He found it in Howard Fast’s historical novel Spartacus. It is a matter of speculation how much Douglas’s Jewish heritage[29] influenced the fact that he made the first ever Hollywood pseudo-historical[30] epic set in antiquity that had nothing to do with both Jesus and/or Christianity. Hollywood, of course, cannot wean from Christianity so they had to stuff it into the off-voice introduction, sounding utterly ironical today, beginning with “In the last century before the birth of the new faith called Christianity, which was destined to overthrow the pagan tyranny of Rome and bring about a new society, the Roman Republic stood at the very centre of the civilized world.” and ends with “There, under whip and chain and sun, he lived out his youth and his young manhood, dreaming the death of slavery 2,000 years before it finally would die”, thus assuming that during 1,900 years Christianity had nothing against slavery, on the contrary, that it supported it wholeheartedly. Of course, Christians would find a prefiguration of Jesus in Spartacus, but Christians are eventually able to find Jesus even on a piece of toast!

The film had a political connotation that is now mostly lost. Not because the political climate has changed, but because it was suppressed in the minds of the people (through the Ludovico treatment?). Spartacus was a giant figure revered in the socialist world and repressed in the capitalist one, because he was the leader of the exploited against the exploiters. With this film Douglas was denouncing the fascistoid blacklisting of Hollywood workers introduced by paranoically deranged USA senator Joseph McCarthy. The cry “I’m Spartacus!” was the cry of solidarity with the persecuted, shunned and haunted. Douglas openly put blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo’s name in the credits, openly defying the Nazi-like House Committee on Un-American Activities. The then USA President John Kennedy, in one of his rare positive moves, crossed a picket line set up by pro-fascist organisers to attend the film.

The slave rebellion is set against the background of the fight for power over Senate and Rome between the republicans, represented by the fictional Gracchus, marvellously played by Charles Laughton, and the pro-dictatorship real-life Marcus Licinius Crassus, played more seriously by Laurence Olivier. However both of those British master thespians are overplayed by another, younger one, Peter Ustinov as Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Vatia, called Lentulus Batiatus by Plutarch, the Roman owner of a gladiatorial school in ancient Capua in which Spartacus’s revolt began. Unlike ironical Laughton and stern Olivier, Ustinov plays his role playfully, like a child included in a game that it adores. It is notable that the three leading roles in Rome are all played by British actors.

There is just one hole in the storytelling: the slave Antoninus’s flight from Crassus to join the rebels. He just seems to disappear from Crassus home, as if there are no guards or servants watching over such an important figure in Rome and his household, only to suddenly appear before Spartacus.

Although Douglas was well aware of Kubrick as a difficult director to work with, he invited him to the recently emptied director chair probably because of the satisfaction with the film the two of them made three years before.

Barry Lyndon (1975) is a picaresque period biography famous for its three period components: period music, period tableaux and period lighting.

Kubrick used music by composers covering the whole of the 18th century, in which the story takes place, from baroque to the classical era, Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach, Georg Friederich Händel, Friedrich II der Große (who, apart from being a King was also a very literate and cultural monarch as well as a good musician, flutist), Giovanni Paisiello, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, as well as borrowing Franz Schubert from the next century. The other kind of used period music is the one that has no era of its own, traditional folk music. This was mainly performed by the legendary Irish group the Chieftains, whose leader Pádraig Ó Maoldomhnaigh (Paddy Moloney) has passed away recently. Also included is military marching music of the era.

The exterior and interior shots were arranged and cinematographed as tableaux inspired by 18th century paintings. The most obvious influence seemed to be William Hogarth, author of some comic strip-like series of pictures called “modern moral subjects”, of which the best adapted to Barry’s life story are A Rake’s Progress and Marriage a-la-Mode. But the works of other portraitists and landscape painters were mirrored as well, those of Jean-Antoine Watteau, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable.

Since his very early films, Kubrick was experimenting with not using other lights but those available at the set. This tendency of his reached its peak in this film, where a lot of scenes unfold in candlelight. By using adequate lenses and film he was able to film them using no other light source and the results are impressive. When combined with the previous two points it gives the film a tone of a faithful documentary on the century in question.

Kubrick engaged another pretty face for his leading role, USA actor[31] Ryan O’Neal. He did a much better job than Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut, simply because his character lived in times when external presentation of emotions, feelings and thoughts was considered not well-mannered.

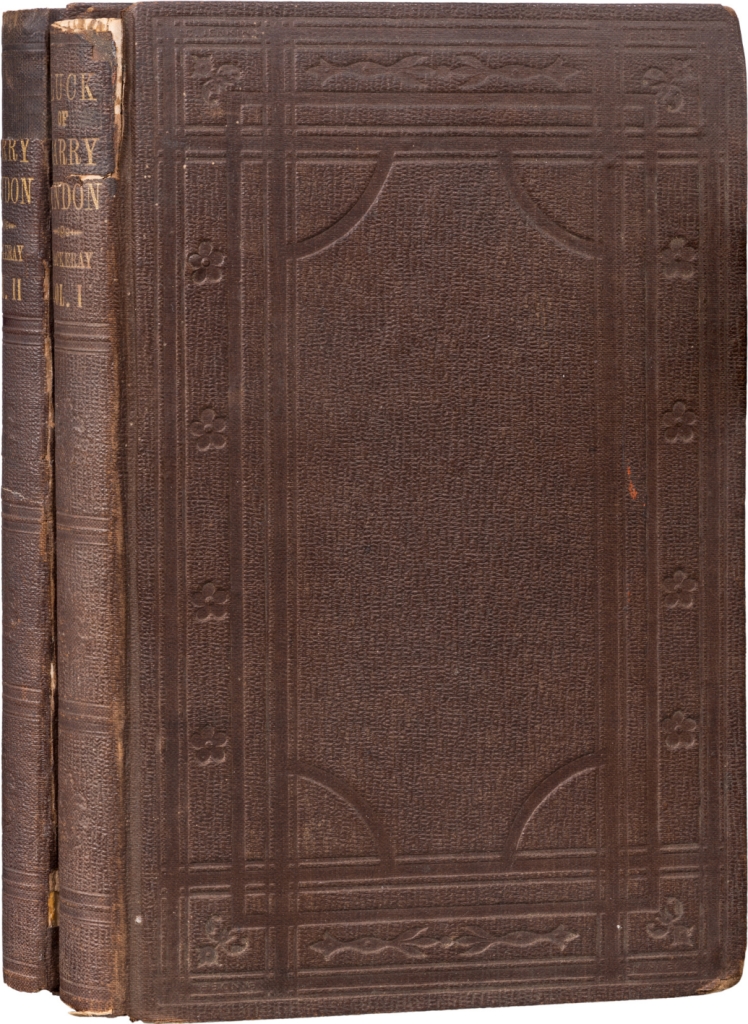

The source for the film was William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. Kubrick divided the life story of the titular character in two parts, Part I: By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon, and Part II: Containing an Account of the Misfortunes and Disasters Which Befell Barry Lyndon, thus telling two different stories of Barry, his ascent from poor country boy to married into money, and his descent into debauchery, indignation and exile. Kubrick was criticised for making A Clockwork Orange’s despicable Alex a character for whom we do care. In this film he had his revenge over the criticisms. In the first part of the film we root for Barry to get out of his misery and become a free man. However, in part two we start rooting against him, we root for all those who try to stop him, we cannot wait for his end to come and it surely does not come too soon. My hatred for him rose to the point that after the final duel I was not sure whether I am disappointed that he should live on or satisfied that he would be punished for life while still alive.

And I know what I am talking about because unfortunately, it was my misfortune not only to know one such verminous worthless piece of shit, but also to have it too close to my family and my home.

The last evening of the retrospective also included two films:

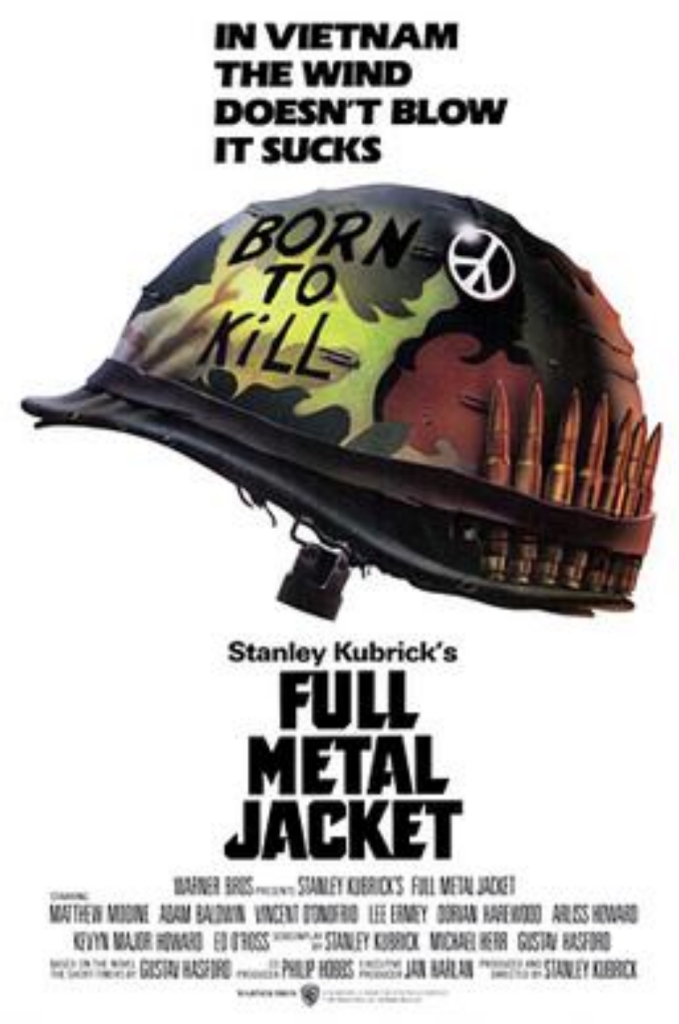

Full Metal Jacket (1987) always reminded my of Robert Aldrich’s 1967 film The Dirty Dozen. Not that the two films have much in common story-wise, except that both are set during wars, separated by a quarter of a century apart. What is shared by the two films are their structures. Both consist of two parts, the training and the action. In both films the training part is better than the action one.

The central characters of the training part of this film are Gunnery Sergeant Hartman and Private Leonard Lawrence, nicknamed Gomer Pyle. Hartman is played with gusto, violently and ardently by real-life ex-Marine drill instructor R. Lee Ermey. He was originally engaged as technical advisor, but when he showed Kubrick what he is capable of doing, he was not only cast for the role, but also allowed to write himself his howling lines of abuse, insults and offenses toward the hapless boys-cum-marines. When I first saw the film, I was unable to recognise actor Vincent D’Onofrio inside the body and mind of Gomer Pyle, although I knew the actor well at the time, such was his metamorphosis into Gomer Pyle. He is a chubby, not quite bright boy, who finds out to be a fine marksman. Gomer Pyle’s inability to perform the most ordinary chores causes eruption of anger from Hartman who pushes him hard, harder than anyone else and who turns the whole company against him by punishing the whole platoon when Pyle makes a mistake. No other role and/or actor in the film comes even close to these two. And when they are both eliminated from the film (you see what I did here?) the whole thing deteriorates.

The action part of the film occurs during the Sự kiện Tết Mậu Thân 1968 (Tết Offensive), a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Kháng chiến chống Mỹ (Resistance War against USA) launched during Tết Nguyên Đán, the Lunar New Year festival, with the date chosen when most Lục quân Việt Nam Cộng hòa (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) personnel were on leave. It was not a military victory for the North, but it was a strong psychological one. One of the major military engagements in the Tết Offensive was the Battle of Huế. After initially most of Huế and its surroundings were liberated, the combined South Vietnamese and USA forces gradually reoccupied the city over one month of intense fighting. The battle was one of the longest and bloodiest of the war, and it had far-reaching consequences due to its effect on the views of the war by the USA public, whose support for the war declined as a result of the offensive casualties and the ramping up of draft calls, and by the world in general.

It is in that mess that Private/Sergeant J. T. Davis, nicknamed Joker, Gomer Pyle’s comrade and personal instructor (by Hartman’s orders), a military journalist, is thrown. Although I have seen the film before and I remember well the training part, the action was as if I saw it for the first time. Not a single memory of it I had except for the hooker scene at its mere beginning. The war scenes were done well and shot perfectly and the key scene has the intended effect, but it all pales when compared to the first half of the film.

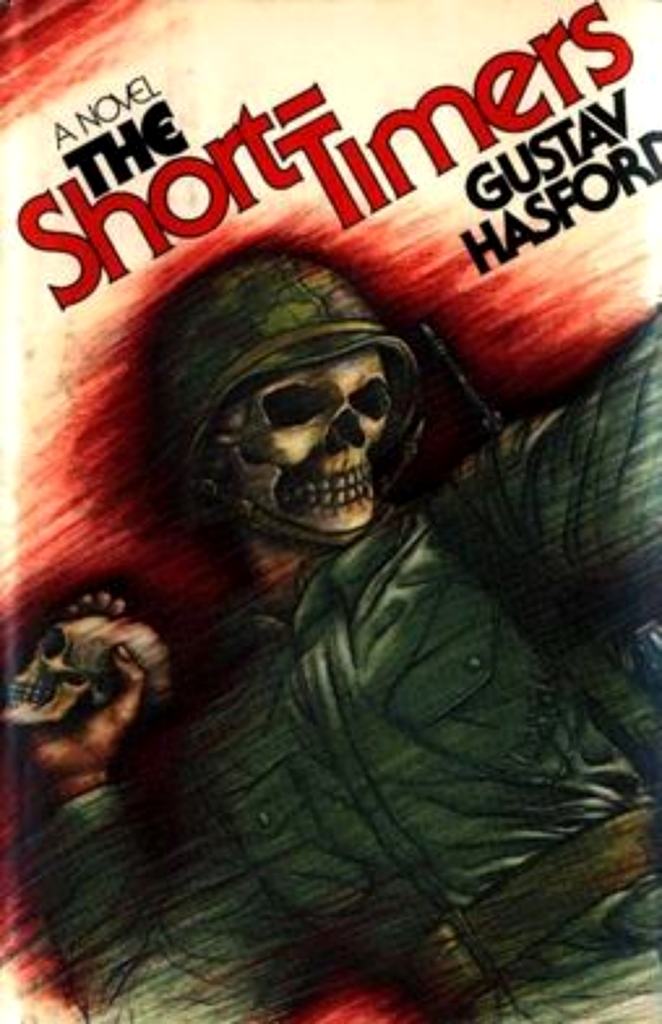

Kubrick was worried that the audience might misread the title of Gustav Hasford 1979 semi-autobiographical novel The Short-Timers that he adapted into this film as a reference to people who did only did half a day’s work and decided to change the title of his film into Full Metal Jacket after coming across the phrase in a gun catalogue[32].

Some topics already dealt with in previous films find their place in this one too. Not only the obvious anti-war and antimilitaristic message. There is also dehumanisation, present in Paths of Glory, Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove, 2001, A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, but also the situation in which craziness and madness take over, like they did with General Jack D. Ripper, HAL or Jack Torrance. Even some characters look similar to some past ones, Animal Mother, the platoon’s combat-hungry machine gunner who mindlessly takes pride in killing enemy soldiers, is not so distant from A Clockwork Orange’s Dim.

Kubrick said in an interview for the New York Times: “Man isn’t a noble savage, he’s an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved ‒ that about sums it up. I’m interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it’s a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.”

The ending of the film shows those marines for what they really are: just little boys, nothing more than brainwashed and well-armed children[33].

Joker is happy because he is still alive and he is going home. But what is he bringing back home with him?

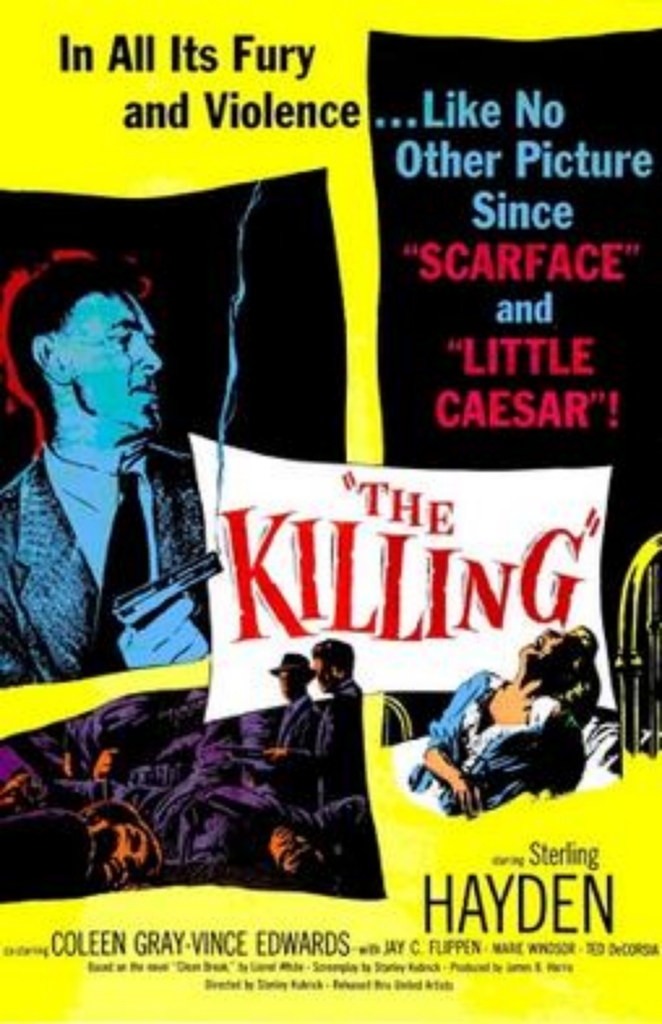

The Killing (1956) is a heist film and usually evaluated as Kubrick’s first great film.

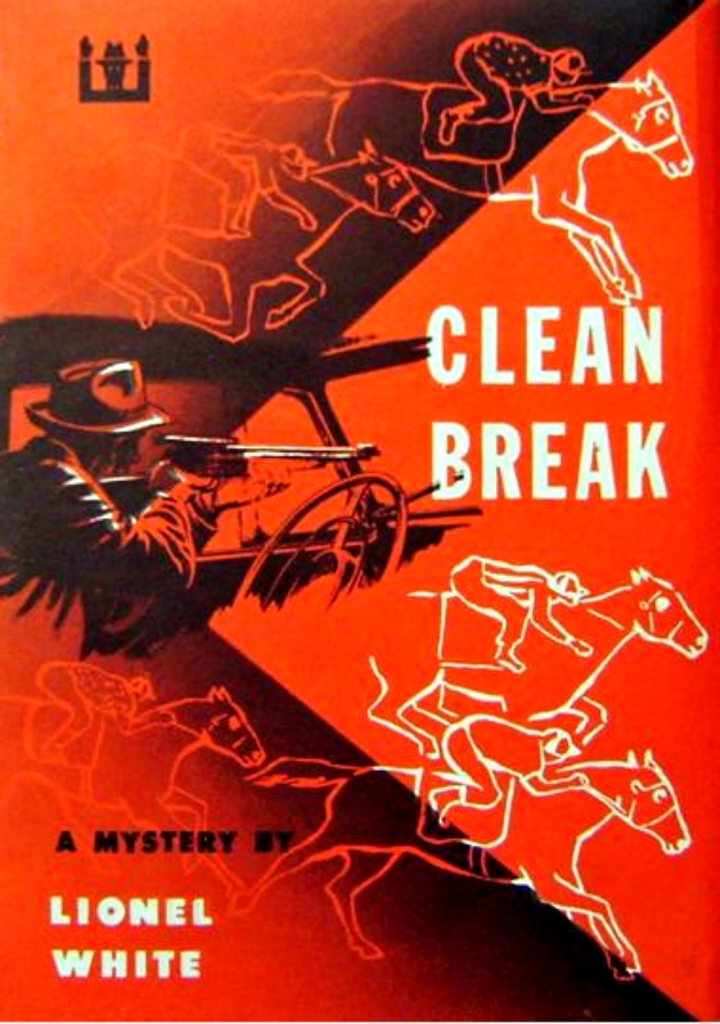

This is the first of three films film co-produced by Kubrick and screenwriter, producer, and director James B. Harris. It was Harris who purchased the rights for journalist and crime novelist Lionel White’s book Clean Break and it was Kubrick’s idea to hire hardboiled crime fiction author Jim Thompson to write the script. For some reason or another, the cinematographer’s union in Hollywood forbade Kubrick to be both the director and the cinematographer, so he never again shot himself a film of his own.

The narrative innovation was connected with the fact that several men had to do their own part at exact times and in exact order for the robbery to succeed. Film critic Roger Ebert compared it to a game of chess (of which Kubrick was an aficionado). Instead of following all the included in a single parallel montage of sequences, Kubrick chose to tell the story of each participant separately. We follow each of the men during the day until the moment their part of the plan enters into action. When we finish following one of them, we go to the next. In this, some scenes are seen multiple times which only enforces the intertwining of the roles each one of them plays in the heist. Quentin Tarantino quoted this film as an influence for his 1992 film Reservoir Dogs, but I would say that the narration style influenced more his 1997 film Jackie Brown (in my eyes still his best one) in which the key sequence is repeated three times, each time following one of the characters involved.

In the film it is only Johnny, played by Sterling Hayden, who knows the overall plot, all the participants, and each involved man’s role. Keeping the whole from others brings to mind Kubrick’s treatment of Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove.

Of course that in the end everything goes wrong. Really, why do heist films always end as failures? Why can honest thieves never be rewarded for their efforts?

The influence of French heist films is pretty obvious, and if I am supposed to call names, I would call that of Jean-Pierre Melville, the French independent filmmaker, mostly of crime films, even elevated by some to the title of being the spiritual father of the French New Wave cinema.

Why do I have the impression of having already seen this film?

Well, that is all, folks!

And how much attending the whole retrospective cost me? Approximately 10% of the average monthly income in this state.

A very good book for Kubrick fans and researchers:

I found it in a second-hand bookshop. As a fan, I bought it immediately. Its only deficiency is that it stops at A Clockwork Orange[34], and it incorporates analyses of only four films: Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange. The other films are mentioned and partly analysed in the two preceding texts, Kubrick: Man and Outlook. From Fear and Desire to A Clockwork Orange (including an interview with the director) and Kubrick: Style and Content.

[1] And the three shorts, 1951’s Day of the Fight and Flying Padre and 1953’s The Seafarers.

[2] Unlike us, the viewers, who saw 12 feature films in 9 days which means 4/3 films per day, that is ¾ days per film.

[3] However, they are not the only ones to show all horrors of war. See footnote 13.

[4] Even The Killing had Sterling Hayden!

[5] False memories shared by multiple people.

[6] The only good thing about this film is hotter than hell Наташа Шнайдер (Natasha Shneider) playing Irina Yakunina, the girl who kittenly snuggled with Floyd during a rough passage of the starship through some atmosphere or other.

[7] Talk about decency among the Catholic( priest)s!

[8] To illustrate the stupidity of PMRC’s record labelling, let us just give a single example. Frank Zappa’s 1986 (and final) album Jazz from Hell got the notorious and ominous label “Parental advisory explicit lyrics”. So what is so stupid about it, you may ask yourself. The mere fact that it was an album of strictly instrumental music!

[9] Sue Lyon was not allowed to see the film she starred in in cinemas until she was eighteen!

[10] Probably connoting that there are also actors without character.

[11] Not everybody is lucky like Frances McDormand or John Goodman to have a Coen brothers to promote them to top acting stars!

[12] Do you not find that in his first dialogue with Humbert Quilty sounds like a typical Woody Allen, who would not make any film for the next four (if you count What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) or seven (if you count Take the Money and Run) years?

[13] Kubrick has demonstrated his anti-war sentiments in other films too, Fear and Desire, Spartacus, Barry Lyndon and Full Metal Jacket.

[14] Is there any way one can defend herself from untrue accusations of sexual harassment, or prove that they are false?

[15] He has probably already risen to his level of respective incompetence, according to Laurence J. Peter, just like Brigadier General Paul Mireau in the film.

[16] A good example is Roman Polanski’s 1976 film Le locataire. In literature, the master of this craft is H. P. Lovecraft.

[17] That is, for me.

[18] The active participant in a syntax structure.

[19] The passive participant in a syntax structure.

[20] Unlike Leonardo DiCaprio, who also started more or less like a pretty face himself to later prove himself as an actor as well.

[21] I am not sure that his alleged family name ever appears in the novel. But I read it some time ago and maybe should go through it again.

[22] By the way, do you know how many symphonies did Beethoven compose? Four: Eroica, the Fifth, Pastoral and the Ninth.

[23] She published her score for the film, only parts of which were accepted by Kubrick for the final film, in 1972 under the title Walter Carlos’ Clockwork Orange.

[24] Similarly, the Catholic Church in my city used all the neighbourhood hooligans, bullies and roughnecks as chief altar boys to keep other altar boys in line.

[25] Diegesis < Greek διήγησις < διηγεῖσθαι ‘to narrate’ is a style of fiction storytelling in which the narrator tells the story, presents the actions (and sometimes thoughts) of the characters to the readers or audience.

[26] Mimesis < Greek: μίμησις < μιμεῖσθαι ‘to imitate’ is a style of fiction storytelling which shows, rather than tells, by means of directly represented action that is enacted.

[27] I bet that Buñuel would enjoy this sequence if he ever had a chance to see it!

[28] Actually, there are, from 1962 to 1965 she played in the TV soap opera Love of Life, she appeared twice in the police procedural series Naked City in 1958 and 1963, she played a film critic in Bob Fosse’s 1979 musical drama film All That Jazz, and could be seen and heard in Jan Harlan’s 2001 documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures.

[29] Born Issur Danielovitch.

[30] The accuracy of some details are questionable. Shaking hands, for instance…

[31] And former boxer!

[32] A full metal jacket (FMJ) bullet is a small-arms projectile consisting of a soft core encased in an outer shell of harder metal called the jacket.

[33] The song they sing probably means virtually nothing to someone who is not from USA.

[34] Well, it was published in 1971!