So what is this “gender” everybody is talking about nowadays?

Gender is a grammatical category characterised by two main properties:

1. it divides all the nominal and some verbal forms into a limited number of categories, so that each word belongs to one of the categories; and

2. it connects words belonging to the same aforementioned category in a sentence or text.

With two caveats:

1. There are words in several languages that seemingly can belong to more than one gender. In French you have aide that can be both ‘male assistant’ (un aide) and ‘female assistant’ (une aide). In BCMS you have bol, which can be masculine ‘physical pain’ and feminine ‘mental pain’. A caveat for the caveat: these are not the same word, these are different words. Belonging to a gender is also a part of the definition of a given word, so belonging to different genders makes them two different words. The same is valid for declension, words belonging to different declension patterns are in fact two different words: masculine bol has the genitive singular form bola, while feminine bol has the genitive singular form boli[1].

2. It is a characteristic of declension as well. Words in the same case are generally connected to each other in a sentence or text.

Another characteristic of gender is that it is a closed category. It is virtually impossible to add a new gender.[2] On the other hand, losing a gender is more common. The late Proto-Indo-European three genders are retained in (among others) Slavic and some Germanic languages, but the Romance languages have in general lost the neuter one, while Armenian has lost gender differences.

So where does a problem with gender arise?

There is also another concept unfortunately also named ‘gender’ that is not related to the grammatical one in any way. It is a social construct that includes the social, psychological, cultural and behavioural aspects of being a man, woman, or other gender identity, where “gender identity” means the personal sense of one’s own social “gender”. This social “gender” was invented in the second half of the 20th century, and is often referred to as only “gender”, without emphasising its non-grammatical connotation.

The problem surfaces when people start mixing and confusing those two different terms.

How could that happen at all?

This confusion began in a de facto genderless language ‒ English. I know, I know that many will raise their voices claiming that English is not genderless, that it has genders, three of them. OK, so tell me, please:

1. what is the feminine (singular) form of the adjective “beautiful”?

2. what is the neuter form of the number “2”?

3. what is the feminine form of “has been”?

Suddenly, those forms happen not to exist. The only remnant of a gender system left in English is present exclusively in one pronoun ‒ that of the third person singular: he, she, it. If that suffices for you to continue your claim that English has genders, answer me another question:

1. does English have cases?

If your answer is no, I simply must remind you that every pronoun has different forms depending on the case they represent: I, mine, me; you, yours, you; he, his, him; she, hers, her; it, its, it; we, ours, us; they, theirs, them. So there are more cases of declension in English than those of gender. If you deny English its cases, you have to do the same, if not even more, with its genders.

So, what exactly does English have? Something usually called natural gender, everything male is masculine, everything female is feminine, and the rest is neuter. Thus, in English it is inconvenient to label someone who does not want to identify as a he or as a she as an it. They say it is insulting, offending.[3]

Luckily, other languages with gender have no such inhibition.

‘Words have sex in foreign parts,’ said Nanny, hopefully.

Terry Pratchett

Witches Abroad

Just for starters, not all languages have the same structure of gender or even the same number of genders. Various languages have from two[4] to a dozen or so genders. In some languages the contrast is between animate and inanimate, or common and neuter, or round and oblong, without any mention of masculine and feminine.

Let us see two examples of gender systems different from those to which we are accustomed:

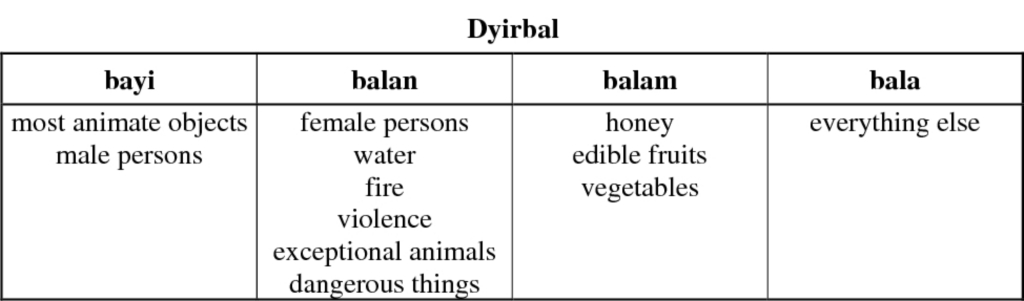

Dyirbal is an Australian language spoken in northeast Queensland by the Dyirbal people, a member of the small Dyirbalic sub-branch of Eastern branch of the Pama–Nyungan language family. The language has four genders[5]:

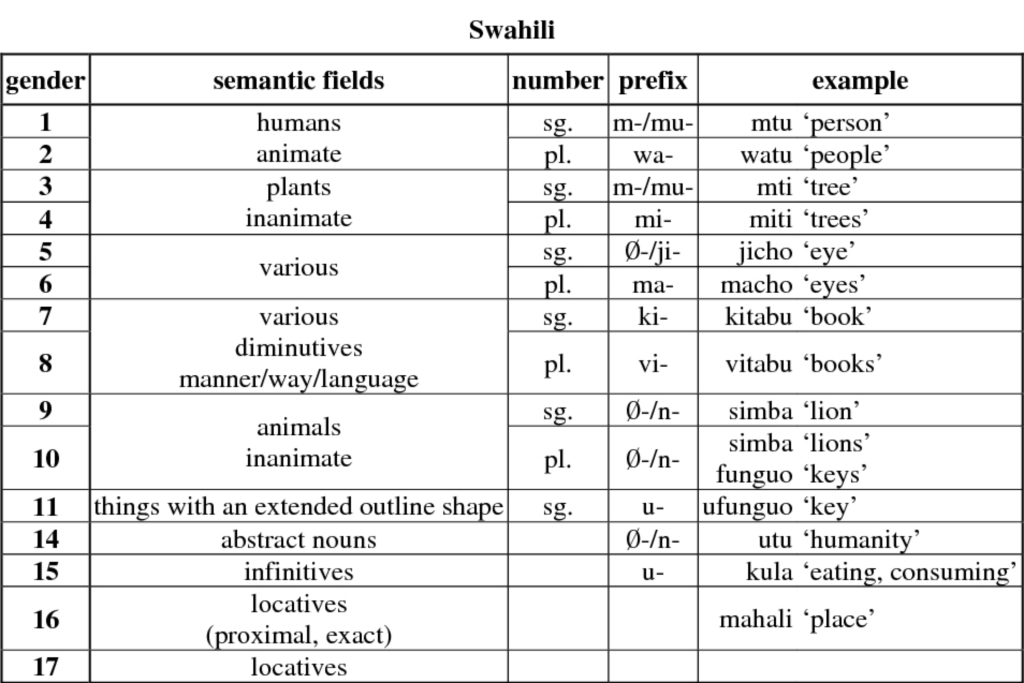

Bantu languages are a language family of about 600 languages that are spoken by the Bantu peoples of Central, Southern, Eastern and Southeast Africa, forming the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages, belonging to the Niger-Congo language family. Bantu languages as a whole have 19 different genders, although some of them present just the singular and plural form of the same one. The Bantu language with the greatest number of speakers is Swahili:

So, as you see, there is enough room for everyone who wants to identify as something else than masculine or feminine.

One must remember that in languages gender is not the same as sex. The most notorious example is German Mädchen ‘young woman’, whose gender is neuter, although the denotate’s sex is most obviously female. The same goes for number in languages, which does not have anything to do with quantity. The best examples is the multitude of English nouns referring to a group of animals of the same kind: a pride (a group of lions), but also luggage and baggage, all treated grammatically as singular nouns.

And yes, languages do have a default gender that is used when the gender of the topic is not known. And yes, in many languages it is the masculine gender. And yes, live with it!

Today everybody is talking about gender-neutral pronouns. OK, you are free to make up new pronouns as much as you wish, like ze, xe, or hir, but you must also be aware that those do not belong to the language until acquired by all, or at least the vast majority of the language’s native speakers. Until then they are just a novelty item. And it is hard to expect other speakers (than yourself) would use them, because it is rather unlikely that they even know that those exist (or even what are they supposed to mean).

Moreover, not all the languages distinguish gender only in the third person singular. Many do it in the plural too. Some languages (Semitic ones, for instance) make a gender distinction in the second persons (singular and plural) as well.[6]

And why just gender-neutral pronouns? Gender-neutral pronouns can function pretty well in genderless languages as English, but are quite inapplicable in languages with a proper gender system. Because in those languages, those gender-neutral pronouns must match other parts of speech possessing gender in some gender-neutrality. So, there should be a whole new category made up out of thin air of nouns (those that can be considered to apply to some “gender”), adjectives, both in singular, plural and any other number forms that the language possesses, numbers (at least those that distinguish the gender), and even verbal forms. As I mentioned in the previous paragraph, Semitic languages differentiate gender in second persons both singular and plural. They do it not only in the pronouns (Hebrew: אַתָּה ‘you (m. sg.)’, אַתְּ ‘you (f. sg.)’, אַתֶּם ‘you (m. pl.)’, אַתֶּן ‘you (f. pl.)’), but also in the verbal forms (Hebrew: כָּתַ֫בְתָּ ‘you (m. sg.) wrote’, כָּתַבְתְּ ‘you (f. sg.) wrote’, כְּתַבְתֶּם ‘you (m. pl.) wrote’, כְּתַבְתֶּן ‘you (f. pl.) wrote’).

So gender-neutrality means much, much more than mere gender-neutral pronouns. It means concocting some new grammatical categories, as I said: out of thin air, virtually inventing a brand new language.

Unfortunately (not for us), languages do not function in that manner.

[1] It happens even when the words are of the same gender, but have different declension patterns. In BCMS sat can mean both ‘clock’ and ‘hour’, but the singular plural of ‘clock’ is satovi and the singular plural of ‘hour’ is sati.

[2] In certain more extreme situations and contexts it can happen, though.

[3] That may be the reason why it is not easy to translate the title of Stephen King’s novel “It” into some languages. You can hit the right gender and still miss the correct meaning.

[4] Languages with “one gender” are in fact genderless.

[5] The balan gender has inspired the title of the 1987 book “Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind” by the cognitive linguist George Lakoff, putting forward a model of cognition argued on the basis of semantics.

[6] I am not sure if there is any language that distinguishes the gender within the first person pronouns, but I would not be surprised if there were.