Is there such a thing as SF music?

I would say that there is.

However, the candidates for that classification could be roughly divided into two categories: music with a SF contents or narrating a SF story, and “space” music, music evoking SF travels through space.

The former group is best represented by concept albums telling some story that could be defined as SF.

The most famous example is Paul Kantner’s 1970 concept album Blows against the Empire, credited to him and the then still non-existing Jefferson Starship. The story of a counter-culture revolution against the oppressions of “Uncle Samuel” and a plan to steal a starship from orbit and journey into space in search of a new home was co-nominated[1] for the prestigious Hugo Award in the category of Best Dramatic Presentation in 1971. The moniker “Jefferson Starship” encompassed an ad hoc all-star line-up including Jefferson Airplane’s Kantner, Grace Slick, Jack Casady and Joey Covington, Quicksilver Messenger Service’s and future Jefferson Airplane’s and Starship’s David Freiberg, Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart, David Crosby and Graham Nash, Peter (Jorma’s brother) Kaukonen and Harvey Brooks. All the songs were written or co-written[2] by Kantner, except “The Baby Tree” by USA folk singer-songwriter Rosalie Sorrels.

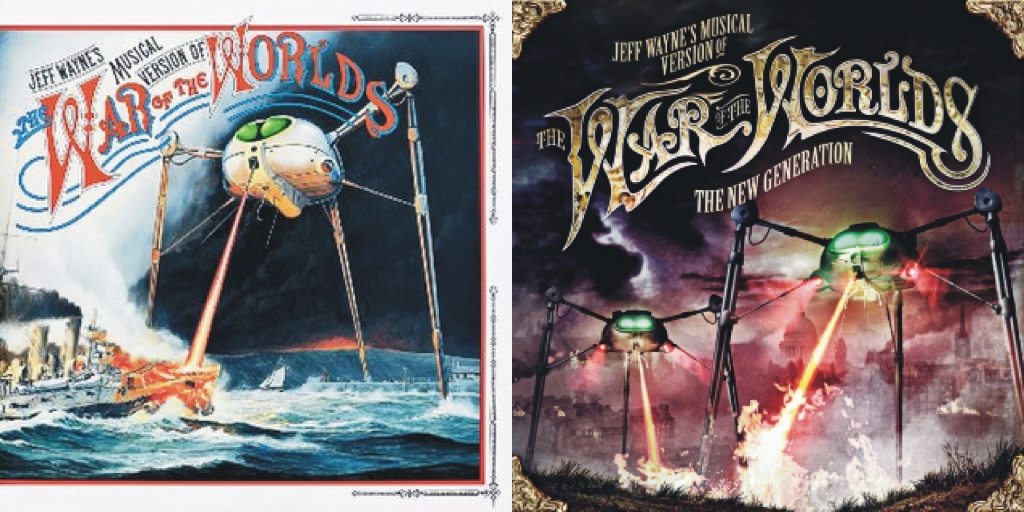

SF concept albums are not such a rarity. In 1978, USA-born British musician, composer, and record producer Jeff Wayne released the double album Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of the Worlds. Wayne and main lyricist Gary Osborne have adapted H. G. Wells’s famous novel as a rock opera with a rock band, orchestra, narrator, and leitmotifs. Wayne also gathered a stellar cast, with Welsh actor Richard Burton as the narrator, plus English singer and actress Julie Covington, English singer, songwriter, and actor David Essex, English guitarist and singer Justin Hayward from the Moody Blues, Irish singer, bassist and songwriter Phil Lynott from Thin Lizzy, and English singer and guitarist Chris Thompson from Manfred Mann’s Earth Band as vocal interpreters. Chris Spedding played the guitar.

Thirty-three years later Wayne revamped the idea by recording Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of the Worlds – The New Generation, re-working the earlier album, and re-creating the score for a new generation of audiences. The narrator is now Liam Neeson, and the singers Gary Barlow from Take That, Ricky Wilson from Kaiser Chiefs, Irish singer, songwriter, and rapper Maverick Sabre, English singer, songwriter and actress Joss Stone, and English singer and songwriter Alex Clare, with Spedding taking over guitar duties again. Unlike the hailed first version, this was received with mixed reactions from critics.

Have you ever heard of Joe Meek? If you have not, you should, because he was one of the most influential sound engineers of all time. Have you ever heard of “the recording studio as an instrument”? Well, Meek was among the first to develop this idea, years before the Beatles discovered it when finally giving up live performances. He was also one of the first producers to be recognised for his individual identity as an artist. To say nothing about him being one of those who assisted in the development of recording practices like overdubbing, sampling and reverberation. Probably his most popular recording is the Tornados’ 1960 Telstar, gaining additional fame as being the first record by a British rock group to reach number one in the USA Hot 100.

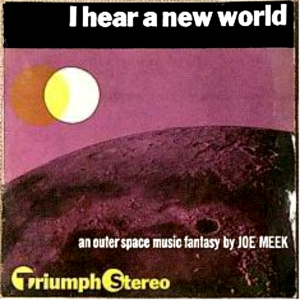

In 1960 he wrote and produced the concept album I Hear a New World, subtitled “an outer space music fantasy by Joe Meek”, with an innovative use of electronic sounds. Alas, the album was not fully released in Meek’s lifetime, because of Triumph label’s financial problems, but only 24 years after his death, in 1991. The music was performed by a six-piece called the Blue Men, originally the skiffle group West Five from Ealing, London, who recorded for Meek under the alias Rodd, Ken and the Cavaliers. Meek was fascinated by the space programme, and believed that life existed elsewhere in the Solar System. He himself expressed his intention to create a picture in music of what could be up there in outer space:

“At first I was going to record it with music that was completely out of this world but realized that it would have very little entertainment value so I kept the construction of the music down to earth.”

Therefore he blended the Blue Men’s skiffle/rock and roll style with a range of sound effects created by purely kitchen-sink methods as blowing bubbles in water with a straw, draining water out of a sink, shorting out an electrical circuit and banging partly filled milk bottles with spoons. It is hard to recognise these sounds on the recording, though, after they underwent his production. This record also represents the early use of stereophonic sound.

Just to help you locate this record in a timeline, in the same year, 1960, the charts were dominated by late, emasculated Elvis Presley (It’s Now or Never, Are You Lonesome Tonight?), Chubby Checker (The Twist), the Drifters (Save the Last Dance for Me) and Johnny Preston (Running Bear). The Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band were 7 years away in the future. Moreover, in 1960, they have just hired Pete Best on drums and went to their first Hamburg residency. They would not publish their first single until two years later.

Then, there are individual songs about some SF topic or other.

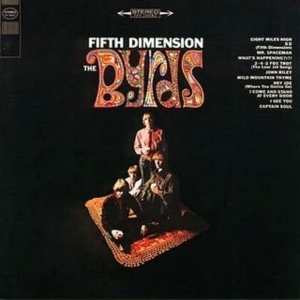

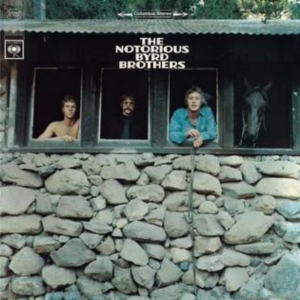

You cannot talk about SF in music without mentioning the Byrds, primarily Jim/Roger McGuinn, a science-fiction buff. On each of the three albums that represent the peak of the band’s career, Fifth Dimension, Younger than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers, McGuinn has written or co-written at least one classic SF song.

Mr. Spaceman was a half-profound contemplation on the possible existence of extraterrestrial life enveloped in some early form of country-rock. McGuinn’s idea of a possibility to communicate with aliens through radio broadcast was smashed by his later realisation that AM radio waves disperse too rapidly in space. He hoped that if the song was played on radio there was a possibility that aliens might intercept the broadcasts and make contact. However, as Polish SF author Stanisław Lem has pointed out in several of his works, the main problem with extraterrestrial intelligent life might not be communication, but simply recognising it as such.

C.T.A.-102 was written by McGuinn and his science-fiction-minded friend Robert J. “Bob” Hippard. It was named after the blazar-type quasar CTA-102. Thematically similar to “Mr. Spaceman”, it was another song that was both whimsical and serious speculation on the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life, although at the same time a somewhat more serious attempt at tackling the subject matter. The space atmosphere has been reached by the extensive use of studio sound effects, simulated alien voices, and the sound of an electronic oscillator. As McGuinn explained the inspiration for the song in a 1973 interview with ZigZag magazine:

“At the time we wrote it I thought it might be possible to make contact with quasars, but later I found out that they were stars which are imploding at a tremendous velocity. They’re condensing and spinning at the same time, and the nucleus is sending out tremendous amounts of radiation, some of which is audible as an electronic impulse on a computerized radio telescope. It comes out in a rhythmic pattern… and originally, the radio astronomers who received these impulses thought they were from a life-form in space.”

Space Odyssey has also been co-written by McGuinn and Hippard. It represents a musical retelling of English science fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host Arthur C. Clarke’s 1951 short story “The Sentinel”. The Moog modular synthesiser is extensively used and the song’s droning, dirge-like melody brings to mind a sea shanty, transporting us from a maritime travel to a space one. As the song predated Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, inspired by the same story, the mysterious object remained pyramidal in shape instead of the better-known monolith from the film and accompanying book.

We should also not forget Pink Floyd, at least before Roger Waters has taken the rains of the band’s recording output in his rigid hands[3].

On their first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, two songs, each introducing one side of the record, deal with space topics, both standing out a bit from the other more fanciful, almost childish lyrics and music.

Astronomy Dominé, written by initial guitarist and leader Syd Barrett, is a great representative of Underground, which was the name often used for UK Psychedelia. It was the band’s first foray in space rock, and it begins with Peter Jenner, one of their managers at the time, reading the names of planets, stars and galaxies through a megaphone. Barrett’s lyrics also mention the planets Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune as well as Uranian moons Oberon, Miranda and Titania, and Saturn’s moon Titan. A perfect little gem of the age, with Waters’s pumping bass, Nick Mason’s relentless drumming, and Barrett’s guitar and Richard Wright’s organ leading the instrumental accompaniment to Barrett and Wright’s vocals.

Interstellar Overdrive is an instrumental written by the whole band, one of the first psychedelic instrumental improvisations recorded by a rock band. It begins and ends with a riff derived from their early manager Peter Jenner humming a song he could not remember the name of[4]. In the middle the song is deconstructed into four parallel solos still keeping (or trying to keep) the same rhythm. Although it sounded like the song burst in four different directions, never to meet again, the band consolidates at the end and finishes the song with the same riff it began with. A fragment of the bass score became the basis for Waters’s song Let There Be More Light, the opening track on the band’s second album, A Saucerful of Secrets.

The latter category of SF music, music that bring to mind space travel or some other notion connected with SF, is usually instrumental.

As Germans called their specific form of late 1960s‒1970s rock Deutsche kosmische Musik (while the rest of the world opted for the more disparaging Krautrock), many of the artist working under that moniker could be included in this article. Let us mention a few of them: Amon Düül, Amon Düül II, Ash Ra Tempel, Can, Cosmic Jokers, Faust, Guru Guru, Harmonia, Kluster/Cluster, Kraftwerk, La Düsseldorf, Moebius und Plank, Neu!, Organisation, Popol Vuh, Conrad Schnitzler, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream and Wallenstein.

冨田 勲 (Tomita Isao) graduated in art history at 慶應義塾大学 (Keio University), Tokyo, at the same time taking private lessons in orchestration and composition. At first he worked as a composer for television, film and theatre. Inspired by Wendy (then still Walter) Carlos and Robert Moog, he turned to electronic music in the late 1960s. In the mid-1970s, he specialised in performing classical music on synthesisers, publishing Snowflakes Are Dancing with music by Claude-Achille Debussy in 1974, Модест Петрович Мусоргский’s (Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky) Pictures at an Exhibition in 1975, and Игорь Фёдорович Стравинский’s (Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky) Firebird in 1976, following in the steps of Carlos’s adaptations of classical pieces for electronic instruments.

His next recording was the 1976 The Tomita Planets, an electronic adaptation of English composer, arranger and teacher Gustav Holst’s seven-movement orchestral suite The Planets, Op. 32, with each movement of the suite named after a planet of the Solar System and its supposed astrological character. 冨田 (Tomita) transformed Holst’s astrology into his own astronautics, beginning the recording with synthesised sounds of the launching of a spaceship that visited the planets as the suite unwinds. Holst’s estate was not happy with the publication of the album, because冨田 (Tomita) did not obtain the permission for the electronic and spacey reinterpretation of the suite by Holst’s daughter, Imogen. She worked hard to prevent the recording being distributed in the UK. Nevertheless, this recording might have been the gateway to Holst’s work, popularising it outside of the usual classical music fans pool.

The couple Bebe (née Charlotte May Wind) and Louis Barron are considered pioneers in the field of electronic music. In 1950, they composed and performed Heavenly Menagerie, the first USA electronic music composed for magnetic tape. In those days composition and production of electronic music were the same thing. The process was time-consuming and arduous. To bring all the sounds needed together, they had to cut the tape physically and paste the cuttings together.

Their claim for fame is the first completely electronic music score for a film, for a SF film, for the legendary 1956 Forbidden Planet, directed by Fred M. Wilcox from a script by Cyril Hume based on an original film story by Allen Adler and Irving Block inspired by William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, with Altair IV, a planet in space, instead of an island, with Professor Morbius and his daughter Altaira instead of Prospero and Miranda, with both Prospero and Morbius having harnessed the mighty forces that inhabit their new homes, with Robby the Robot instead of Ariel, with the powerful race of the Krell instead of Sycorax, with the dangerous and invisible monster from the id, a projection of Morbius’s psyche born from the Krell technology instead of Caliban, a projection of Sycorax’s womb. The film was a pioneering effort within the genre of science fiction cinema: the first science fiction film to depict humans travelling in a faster-than-light starship of their own creation, the first science fiction film to be set entirely on another planet in interstellar space, far away from Earth, presenting Robby the Robot as one of the first film robots that was more than just a mechanical tin can on legs. And last but not least, the special effects were groundbreaking.

For such a groundbreaking SF film, preceding the key oeuvre in the genre, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, for 12 years, a similarly groundbreaking score was needed. And that is exactly what the Barrons delivered: such a creepy and ominous soundtrack was never heard before by any film-going audience. Initially, it was composer, music theorist, and creator of unique musical instruments Harry Partch who was chosen to write the score, with the Barrons simply commissioned to do only about twenty minutes of sound effects. These twenty minutes were sufficient to convince the producers to transfer the complete score duties to the couple.

As Bebe and Louis explicate on the soundtrack album sleeve:

“We design and construct electronic circuits [that] function electronically in a manner remarkably similar to the way that lower life-forms function psychologically. […]. In scoring Forbidden Planet – as in all of our work – we created individual cybernetics circuits for particular themes and leitmotifs, rather than using standard sound generators. Actually, each circuit has a characteristic activity pattern as well as a ‘voice’. […]. We were delighted to hear people tell us that the tonalities in Forbidden Planet remind them of what their dreams sound like.”

Again, let me help you with some time perspective: in 1956, the USA charts were dominated by Dean Martin’s Memories Are Made of This, Kay Starr’s Rock and Roll Waltz, Nelson Riddle’s Lisbon Antigua, Les Baxter’s The Poor People of Paris, Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel, I Want You, I Need You, I Love You, Don’t Be Cruel, Hound Dog and Love Me Tender, Gogi Grant’s The Wayward Wind, The Platters’ My Prayer and Guy Mitchell’s Singing the Blues.

Writing about SF music and not mention English musician and composer of electronic music Delia Derbyshire would not be a sin, but a serious crime. During the 1960s she was a notable member of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Referred to as “the unsung heroine of British electronic music”, she has influenced musicians like Irish-born British musician, composer and DJ Aphex Twin, the English electronic music duo Chemical Brothers and Paul Hartnoll of the English electronic music duo Orbital. However, during her career, especially at its beginning, she was discriminated against for being a woman. When she applied for a job at Decca Records, they infamously answered that they refuse to hire women for work in their recording studios. After stints with United Nations in Geneva and the London music publisher Boosey & Hawkes, she became a trainee studio manager at the BBC in 1960, leading to her involvement with its then-young Radiophonic Workshop, that was primarily intended to supply incidental music and sound effects for Radio Drama productions. Even there she did not find a supportive environment, as much of her work was rejected for being either too lascivious for youngsters or too sophisticated for many adults. Therefore, with fellow composers, including Brian Hodgson, David Vorhaus, and Peter Zinovieff, she set up a number of studios (Electrophon, Kaleidophon, and Unit Delta Plus), where she could develop freely in avant-garde circles and delve further into work for film and theatre. She was one third of White Noise, an English experimental electronic music band (the orther two thirds were Vorhaus and Hodgson), that published its debut album An Electric Storm in 1969, now considered important and influential in the development of electronic music. Frustrated with the state of music and the prospect of where it was headed, Derbyshire left the Radiophonic Workshop in 1972.

Her call to fame was the original opening tune of the British SF series Doctor Who, one of the firstelectronic music signature tunes for television. It has not lost its popularity even after more than half a century from its first appearance and it is still regarded as a significant and innovative piece of electronic music. Mind you, this piece was constructed well before the availability of commercial synthesisers or multitrack mixers. This means that each note was created individually by cutting, splicing, speeding up and slowing down segments of analogue tape containing recordings of a single plucked string, white noise, and the simple harmonic waveforms of test-tone oscillators, that were never intended for creating music, but for calibrating equipment and rooms. Before the era of multitrack tape machines, new techniques had to be invented to allow mixing of the music.

Many mistakenly believe that she was also its composer. Well, she was not. It was composed by Australian composer Ron Grainer, author of theme music for some other UK television series, The Prisoner, Steptoe and Son and Tales of the Unexpected. Delia only arranged it and realised it aurally, with assistance from British sound engineer Dick Mills. The theme was released as a single on Decca F 11837 in 1964. Her arrangement served, with minor edits, as the theme melody for 17 years, to the end of season 17 (1979–1980).

When Grainer heard the finished track, he allegedly asked, “Jeez, Delia, did I write that?” She answered laconically, “Most of it.” Grainer was willing to give Derbyshire the co-composer credit, but that would come into conflict with the then BBC policy.

Derbyshire would receive her first on-screen credit for the music only in 2013, at the 50th-anniversary story The Day of the Doctor with three Doctors present, the Tenth, the Eleventh and the War one.

Of course, there are, there must be more…

[1] The other nominee was USA surreal comedy troupe Firesign Theatre’s third comedy album Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me the Pliers, about the five ages of former child actor George Leroy Tirebiter who watches himself on TV.

[2] The co-writers were ex-Jefferson Airplane’s Marty Balin, Gary Blackman, Covington, Crosby, Garcia, Hart, Nash, Phill Sawyer, and Jefferson Airplane’s and future Jefferson Starship’s and Starship’s Grace Slick.

[3] Mind you, on their first album, he wrote just one song and co-wrote two with the rest of the band.

[4] Most likely Love’s cover of Burt Bacharach’s and Hal David’s My Little Red Book