Hoffmann Ferenc was born in Budapest in the days when Austro-Hungarian admiral Horthy Miklós ruled as the Regent of the re-established, but kingless Kingdom of Hungary. After surviving Nazi concentration camps in World War two he re-appeared in Budapest as Kishont Ferenc. Eventually, when he immigrated into Israel, an immigration officer finally made him who we all know now very well ‒ אפרים קישון! Yes, ladies and gentlemen, Ephraim Kishon.

קישון (Kishon) is primarily known as a writer, a satirist. During his half a century long career he published dozens of books collecting his short stories and some novels. But he was more than that. He was also a dramatist, a theatrical person and ‒ what is more important in this context ‒ a screenwriter and film director.

In his thirteen-year long film career he wrote and directed five satirical feature films.

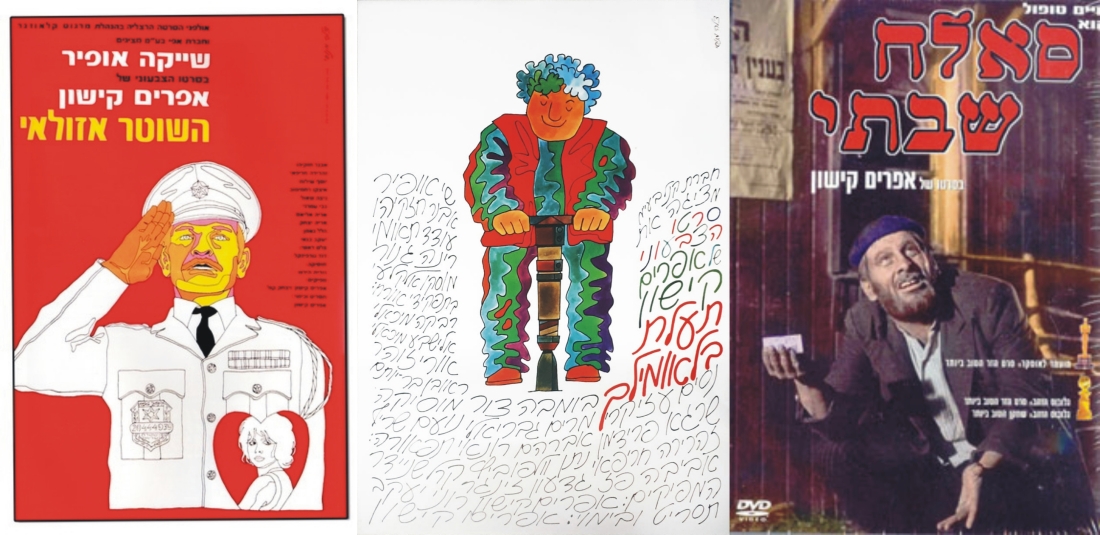

Three of those were recently shown in a retrospective in the local art cinema/cinemathèque, his first, third and fourth.

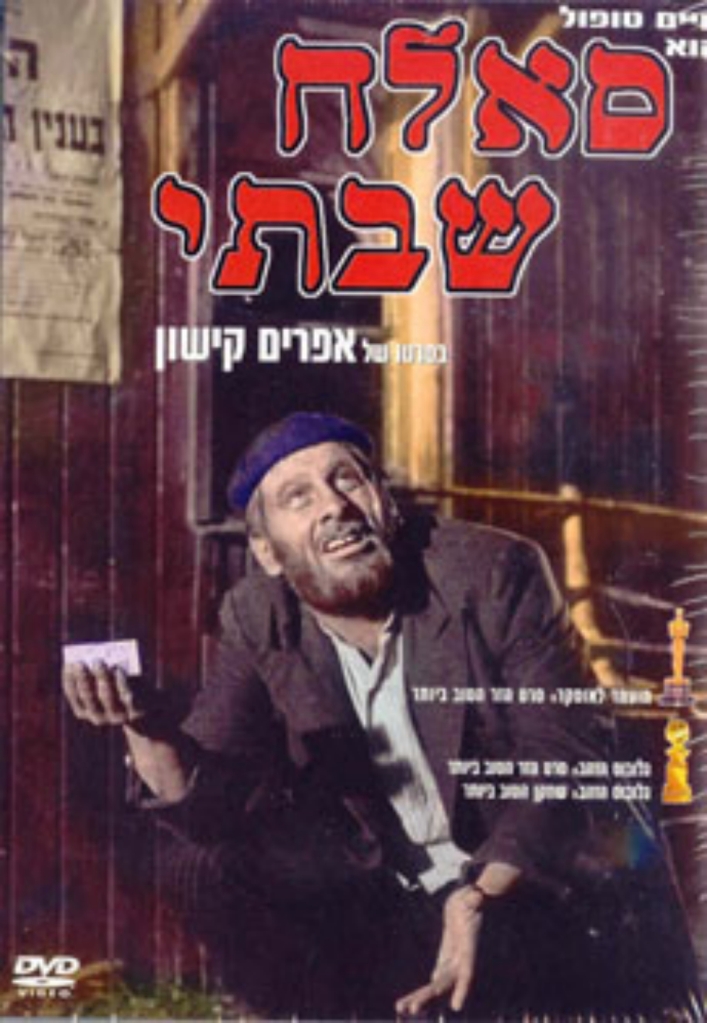

The film סאלח שבתי (Sallah Shabati) was made by Kishon (קישון) in 1964 as his big screen debut, and it shows. It is still a little bit rough around the edges. It tells the story of the eponymous Mizrahi Jew, that is a Jew from somewhere in the Middle East, immigrating into the new Israeli nation with his pregnant wife, six or seven children (has not counted them lately) and an old woman whom nobody knows who she actually is but has been with the family forever. They are assigned a ramshackle one-room hut in a מעברה (ma’abara) or transit camp within a קיבוץ (kibbutz). Temporary, of course. However, this temporariness might last for a serious length of time, as proven by the family’s neighbour גולדנשטיין (Goldstein), with whom סאלח (Sallah) kills time by playing שש בש (shesh besh, the Middle Eastern variant of backgammon). For money, of course. And סאלח (Sallah) wins every time, of course. But he does not want to live in a shack. He wants to live in an apartment, like the ones built nearby. However, for the apartment, he needs money, and lot of it. Working for it is out of the question. A daughter sold as bride seems like an easy solution…

The film promoted חיים טופול (Chaim Topol) in the title role as a talented actor (he convincingly played a person twice his age)[1] to worldwide audiences[2] as the film achieved international success, being the first one from a fledgling Israeli cinematography to do so. A young kibbutznik, the love interest of the main character’s eldest daughter חבובה (Habuba) is played by אריק איינשטיין (Arik Einstein) who is going to become a famous Israeli singer, songwriter, actor, comedian and screenwriter. איינשטיין (Einstein) is the author of the first Israeli rock album, the 1969 פוזי[3].

As קישון (Kishon) manages to insert at least one Israeli beauty in his films, in this one, as far as I am concerned, this role is taken over by the קיבוץ (kibbutz) social worker בת שבע (Bat Sheva) played byגילה אלמגור (Gila Almagor).

קישון (Kishon) was heavily criticised for him, an Ashkenazi Jew, poking fun of Mizrahi Jews. However, it is also true that the pompous heads of the קיבוץ (kibbutz), the קיבוץ (kibbutz) secretary נוימן (Neuman; note the Ashkenazi family name!), played by שרגא פרידמן (Shraga Fridman), and the קיבוץ (kibbutz) supervisor פרידה (Frida; note the Germanic first name), played by זהרירה חריפאי (Zaharira Harifai), are no less caricatured than סאלח (Sallah) himself. It is actually a typical culture clash comedy, depicting the reality of Israel as melting pot of different Jewish traditions. As is the custom in comic situations where people from rural areas move to urbanized ones, סאלח (Sallah) has no intention of adapting to the new environment. On the contrary, the new environment must be the one to adapt to his ancient ways. In this way, he shares a lot with the title character of Dušan Kovačević’s comedy Radovan Treći (Radovan the Third), a man who left his zavičaj[4], but who cannot make his zavičaj leave him.

When immersing oneself in Israeli culture, one should be well-informed about the relationships within the Israeli reality. Israel was founded by Ashkenazim who fled Europe after the horrors of WWII and השואה (The Shoah). Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews immigrated mostly after being expelled from predominantly Muslim states by their Muslim governments. The imbalance of power between the former and the latter is either the main topic or the background of many Israeli narratives. In סאלח שבתי (Sallah Shabati) this inequity of power is ridiculed not only between the Ashkenazi קיבוץ (kibbutz) leaders and the Mizrahi Jew but also among the קיבוץ (kibbutz) leaders themselves, as פרידה (Frida) turns out to be the real controlling power in the קיבוץ (kibbutz). The caricature of קיבוץ (kibbutz) functionaries is especially obvious when the secretary shows the planting of trees to a benefactor whose name the future forest will bear only to show it to another benefactor shortly afterwards as a future forest bearing his name.

It is a black and white film and, as I said, the first one made by קישון (Kishon), so it should be taken at that value.

The film was nominated for Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1965. The winner was Vittorio de Sica’s Ieri, oggi, domani (Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow) and the other nominees were Bo Widerberg’s Kvarteret Korpen (The Korpen Neighborhood), Jacques Demy’s Les parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) and 砂の女 (Sand Woman) by 勅使河原 宏 (Teshigahara Hiroshi).

By the way, most of films that קישון (Kishon) made were not based on original screenplays, but adapted from some other media. Just like Jaroslav Hašek’s Švejk, סאלח (Sallah) lead a pre-life in several stage sketches and short stories. Of the film’s motivation and success the author writes in his book Almost the Whole Truth, dealing with the inspiration behind his short stories, novels, plays and films:

It is a common misconception that Hollywood filmmakers are heartless people. In fact, they are all like that all over the world.

In Hollywood there sit a few fat gentlemen with cigars between their teeth buying anyone they like. They just buy him.

My films have been among the top five Oscar-nominated foreign films twice. I never got it. Both times I was very sad. The great director William Wyler gave me a good advice: “Do you want to save yourself from such disappointment in the future? Make bad movies!”

I have experienced the above-mentioned procedure [of Hollywood buying anyone they like] myself several times. The greatest ordeal followed my film Sallah about the Arab-Jewish immigrant Sallah Shabati. The film won the Hollywood Film Critics Award and was nominated for an Oscar. Then the producer of the most successful American TV series, a shy man of German descent, ordered from me a series of 24 one-hour sequels in which the protagonist would be a somewhat Americanized Sallah… I began to calculate aloud:

“24 hours, that means three years.”

The producer replied:

“No, my friend, that means a million dollars.”

It took me a few minutes to make a decision. (I couldn’t help but to silently ask forgiveness from my grandchildren, who will have to work somewhat more because of it…)

“Rest assured,” I told the Hollywood mogul, “that I have a burning desire to work in your grand studios. I would love to settle in Hollywood and become one of your men. But my weak character stands in the way of my great desire ‒ I long for home, Israel. That’s where the big money is.”

I bet that the producer is still sitting there with his mouth ajar. And I returned to Israel, a land of limited possibilities where Sallah is no TV hero, but a very living nudnik.

It’s hard to emigrate. It’s even harder to immigrate.

I met Sallah in my pioneer days, a few weeks after arriving in the Jewish state founded only a few months earlier. A million more refugees came with me, so there was quite a crowd, they put us in the settlements of barracks knocked together quickly, fifteen souls in one room. Of course, only temporarily, for a maximum of five or six years. I found myself in a huge camp near Haifa, in a shack made of red-hot corrugated iron. In one corner of the barn my wife and I were lying on straw, and in the other corner laid an unshaven Moroccan with a round wife and countless offspring. There was also an old woman who was doing laundry all the time.

Sallah was an Arab Jew. His grandchildren will be Jewish Arabs.

At first, there was tension and mistrust between Sallah and me, but as we got to know each other a little better, our relationship became extremely hostile. Sallah was a fat man who hid his years under a carefully ungroomed beard. In addition to Arabic, he spoke fluent French, but he was one of the most primitive blokes I have ever met. And one of the most intelligent ones as well.

The few conversations we had in the hot hut gave me material for a stage character who, in the interpretation of the outstanding actor Topol (also known as Tevye from the film Fiddler on the Roof), not only won countless film awards, but one can no longer imagine Israeli folklore without him. Sallah was a conman, a liar and a charmer in one person, all of a very special kind. When I asked him, for example, how many children he had, he started counting them. He didn’t know it by heart. When I asked him about his occupation, he replied that he was a train driver.

“Which line are you driving on?” I asked him.

“I haven’t driven yet. I didn’t have the time to learn it.”

As I said, he was a bit of a peculiar guy. He could not give any reliable information about the grandmother who permanently did some laundry or other. He said he didn’t know who she was. Yes, she has always been with them, that is true. Was she related to him? Maybe, how would he know?

Women in the Middle East are only allowed to speak when their husbands allow it. No such case has been reported so far.

Sallah’s plump wife squatted day and night against the red-hot tin wall and was silent as a grave. No one would have heard her in the middle of that children’s roar anyway. When I invited Sallah to discuss some basic principles of hygiene, Mrs. Sallah came to the door of the shack and shouted to her husband:

“Sallah! The powers that be want to talk to you!”

The misery of the camp residents was indescribable. In those heroic and terrible times, there was bread on consumer cards only, if there was any. Everything was bustling with hungry beggars. Only one of us figured out in two weeks how to cash in on his poverty.

“Mr. Sallah Shabati?”

“That’s me. Do you speak French or Arabic? Yes? Then come in, sir, and sit down. Yes, there in the corner. On that broken box.”

“Thank you very much.”

“If the kids bother you, I can strangle them.”

“It won’t be necessary.”

“Okay, then I’ll lock them in the bathroom. Shoo, shoo! So. Are you a reporter for a daily newspaper or magazine?”

“Daily newspaper.”

“With a weekend supplement?”

“Yes, Mr. Shabati. I read your ad in our paper: ‘Poor fam. with 13 ch. on disp. for the mass media’. Do you have time for me now?”

“An hour and 15 minutes. I already gave an interview to the radio this morning, and after you some kind of investigative committee will come, but we can talk now.”

“Thank you, Mr. Shabati. My first question…”

“Don’t be in such a hurry, wait a minute. How much do you pay?”

“Say what?”

“I’d like to know what my fee will be. I guess you don’t think that I’m squatting in this dilapidated shack out of pleasure, or that I might be living on state support with my family?”

“I didn’t even think about that.”

“But I did. The catastrophic situation of primitive oriental settlers has a fairly high market value today. The ones in this position should also benefit from it. Let’s say you write a nice report with an air of the poor, unhygienic conditions and so on, it will attract attention, it will help sell your newspaper and affect your salary. In addition, you’ll gain the status of a socially engaged journalist. And I will help you as much as I can, sir. From me you’ll receive a touching depiction of my woes, my disappointment, my indignation, my…”

“How much are you looking for?”

“My usual rate is £ 300 an hour, plus VAT. With photos 30 percent more. Payment in cash. I don’t accept checks. I do not sign any receipts.”

“£ 300 an hour?”

“I still have to pay my manager from that sum. Such are the tariffs today, sir. In the Yemeni neighbourhood, you may find some desperate man for 150 pounds, but what a desperation that is! Eleven children at most, all well fed, and decent monthly welfare allowance. And with me you have a family of nineteen members on 55 square meters of living space, with three grandmothers and with this unhappy married couple in the corner.”

“And where is your wife?”

“She’s just being photographed up on the roof. Hanging laundry on our antenna. She is also pregnant.”

“Then you should receive a supplement to the state aid?”

“I gave up both. That could hurt my position in the market of misery. Interviews bring more. These days we will be moving to an even smaller, more dilapidated hut. With probably another goat. And where is your photographer?”

“He’ll be here any minute.”

“As for the design of the text, I would like it to go on two adjacent pages. And the title across both pages.”

“Don’t worry, Mr. Shabati! We will take care of your wishes.”

“Good. And now, sir, we can begin.”

“My first question: do you think, Mr. Shabati, that you are being treated badly in Israel?”

“Why? I am sincerely grateful to my compatriots. They have a heart of gold. However, they do not work hard to fight poverty and no one cares about the slums in their city. On the other hand, the public shows lively compassion for us and is always unusually touched when they see photo-documentation of our misery in illustrated magazines. This is by no means without consequences. If you could only hear all those professors and sociologists when they begin to cluck! Their words are really soothing. And the need of the mass media for reports of misery is still growing, so that the standard of living of us socially disadvantaged is constantly improving. It could be argued that Israel is the first country in the world to solve its social problems through interviews.

The conflict between European and Oriental Jews was programmed from the very beginning. The solution is called – mixed marriages. The quarrel would not stop though, but at least it will remain in the family.

This sarcasm at the end is mine, but the patent is Sallah’s. The laziest Moroccan fox was a born living artist. In the winter, when all the inhabitants of the camp had been shaking since November, Sallah went to work at the nearest market and returned in two hours with a brand new oil stove that he had stolen somewhere. He placed it as far away from us as possible so that the precious heat would not be wasted on two low-income Europeans. Only our winter coats protected my wife and me from the cold. When I caught a cold one day, a devout camp doctor gave me a hot water bottle. (He thought I was a good believer because he once happened to see me buying candles.) It was an oversized hot water bottle, made in Sudan, pink with green dots. Soon I couldn’t do without it anymore, I dragged it everywhere with me.

(Retranslated by me.)

The third film made by קישון (Kishon) was תעלת בלאומילך (The Blaumilch Canal) from 1969, that for some unfathomable reason was rechristened The Big Dig in the Anglophone world.

I can say that this one was my favourite of the whole programme, mostly because of its absurd and at time surrealist setting.

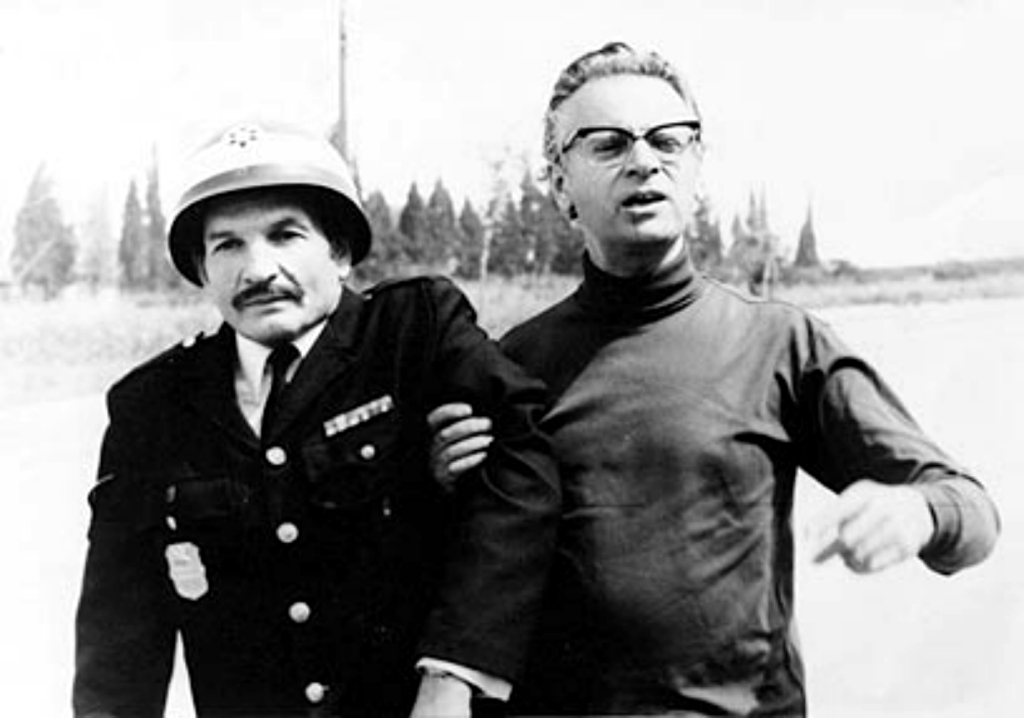

The story is quite simple: קאזימיר בלאומילך (Kazimir Blaumilch), a lunatic known as החפרפרת (the Mole) because of his digging mania, digs his way out of an asylum, steals a pneumatic drill and an air compressor, drags them to the junction of רחוב אלנבי (Allenby Street), רחוב בן יהודה (Ben Yehuda Street) and רחוב פינסקר (Pinsker Street) and starts digging. The inhabitants of the neighbouring buildings are the first to protest for the noise. The location being one of the busiest traffic hubs in תל־אביב (Tel-Aviv), drivers are the next to kick up a row. Soon an incompetent policeman, played by שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir) tries to bring some order, only to embiggen the chaos. The city officials in charge of road maintenance have no idea who ordered the works but have no intention whatsoever to admit that something might go on in their department without their knowledge so they join their own machinery and workforce to speed up the construction (or destruction). Eventually, the digging reaches the Mediterranean Sea, רחוב אלנבי (Allenby Street) is flooded, then transformed by the politicians into a canal, with the mayor inaugurating it proclaiming תל־אביב (Tel-Aviv) “the Venice of Middle East”[5]. In short, politicians turn their own incompetence and ignorance into a triumph!

The situation brings to mind the famous Hauptmann von Köpenick, the shoemaker Friedrich Wilhelm Voigt who, in 1906, masqueraded as a Prussian military officer, rounded up a number of soldiers under his “command”, and “confiscated” more than 4,000 marks from a municipal treasury. No one dared oppose him because everybody was trained to obey a military officer without questioning. In the film, nobody questions the acts of a lunatic.

I mentioned surrealist humour. One of the best such sequences is when two heads of the Municipal Road Department, אביגדור קויבישבסקי (Avigdor Kuybishevsky) and זליג שולטהייס (Zelig Schultheiss) have a heated argument about responsibilities, hiding facts from each other and undermining each other that was in real danger to turn into a fistfight, interrupted by the secretary announcing a tea break. What ensues is an idyllic scene in which best friends ‒ what am I saying? loving brothers and sisters enjoy their tea with almost an erotic intimacy. Then the tea break ends, the participants move to the places they occupied before the break and continue with the quarrel exactly where they were so unrudely interrupted.

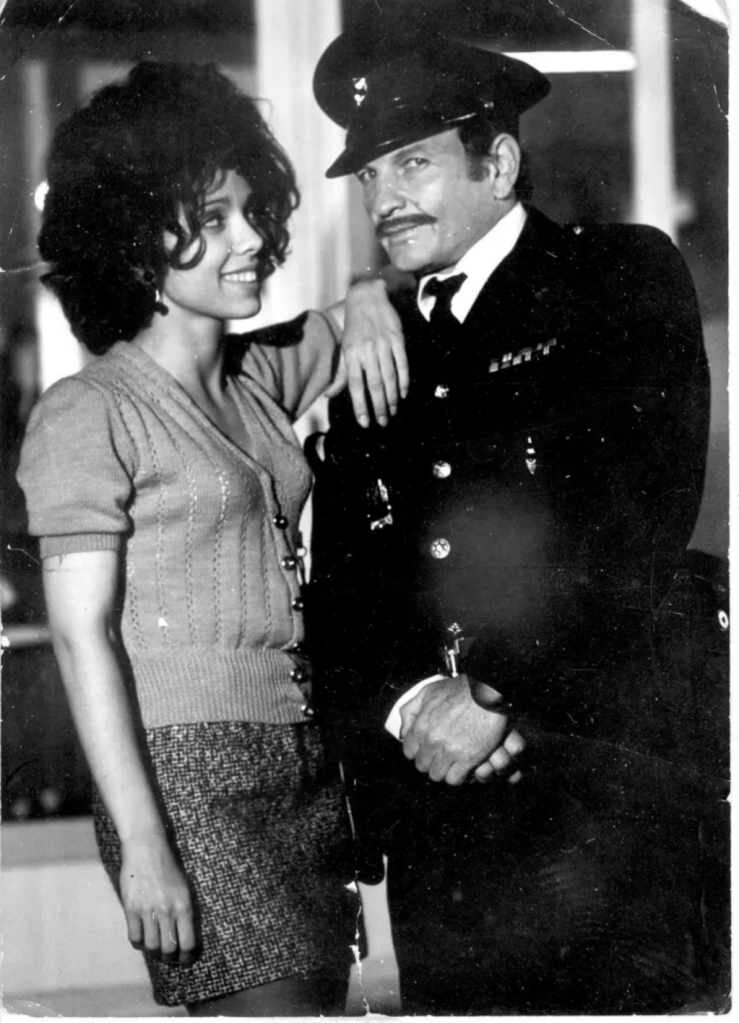

When I mention the secretary, she is the nameless secretary of קויבישבסקי (Kuybishevsky). She is totally unable to type, which is effectively demonstrated in a short gag, but has other qualities (competing with Candy del Mar in making bubblegum balloons, for instance). Among those are a skimpy mini dress and azure satin knickers, which she loses somewhere in the middle of the film. We do not actually see her without them on ‒ קישון (Kishon) is not that kind of director! ‒ but their story is told marvellously in three short frames. Blink thrice and you will miss it. First we see them on her thanks to the enormous shortness of the dress and her own way of sitting on a chair. Next they are found in a cigarette case, grabbed by קויבישבסקי (Kuybishevsky) tucking them into the inside pocket of his jacket. Finally we see him pulling them out again to wipe the sweat from his forehead. A sweet erotic joke perfectly told in film language.

This secretary, played so provocative and yet not pornographically or vulgarly by Aviva Paz (אביבה פז), is the sexy Israeli beauty in this film.

Watching the movie one cannot help asking oneself how the גיהנום did קישון (Kishon) manage to do it. I mean, you cannot destroy a city centre just to make a film. Or can you? Eventually it turns out you cannot. קישון (Kishon) had the whole thing (the whole street and the 30 m canal!) reconstructed on the beach behind the film studios in הרצליה (Herzliya).

The film was nominated for Golden Globe for Best Foreign-Language Foreign Film in 1969. The winner was Costa-Gavras’s Z and the other nominees were Bo Widerberg’s Ådalen 31, Κορίτσια στον Ήλιο (Girls under the sun) by Βασίλης Γεωργιάδης (Vasilis Georgiadis) and Federico Fellini’s Fellini Satyricon.

The penultimate film that קישון (Kishon) made was the 1971 השוטר אזולאי (Constable Azulay), which was also rechristened in English as The Policeman for reasons unknown.

Inspired by how capably שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir) played an incapable police officer in his previous film, קישון (Kishon) decided to dedicate a whole film to such a character. The policeman got a name, אברהם אזולאי (Avraham Azulay), and a third dimension. אזולאי (Azulay) is a bad copper, but not for the same reasons the character played by Harvey Keitel in Abel Ferrara’s 1992 film Bad Lieutenant is. Au contraire. אזולאי (Azulay) is a bad copper because he is a good person. This could be a morale of the whole story: A good man is a bad copper. He sees people for what they are and not what they represent. Unlike his colleagues, he believes in human goodness and dislikes solving problems with violence. That is the main reason why he never ever advanced in position in twenty years in the force. Instead of attacking a group of orthodox Jews who stone cars that are driven on Saturday, he enters with them in a friendly religious debate and calms them down[6]. When the delegation of the French police force visits his police station, as the only one who speaks French, he mellows down the occasional harsh remark and is adopted by the French as their buddy and guide.

However, there is a Damocles’s sword hanging over the head of אזולאי (Azulay) the whole time: his superiors want to get rid of him, and he himself is not sure whether he would like to have his contract extended or not, and what about that long-awaited promotion? His superiors, פקד לפקוביץ׳ (Captain Levkovich) and סמל בז׳רנו (Sergeant Bezherano), another pair of pompous functionaries, eventually decide to finally dismiss him. This alarms the underworld in the area patrolled by אזולאי (Azulay) because his presence there helps them a lot with their businesses, whereas a more diligent copper in the neighbourhood could bring them harm. What אזולאי (Azulay) needs is solving a major crime. And they will make it happen, like it or not.

This solution brings to mind another classic comedy, Steno’s and Mario Monicelli’s 1951 film Guardie e ladri (Cops and Robbers[7]). Ferdinando Esposito played by Totò is a small crook who tries to support his family by conning people. His arch-enemy is Sergeant Lorenzo Buttoni played by Aldo Fabrizi, who is too fat to be able to catch him. However, Buttoni’s superiors give him an ultimatum: either he will finally arrest Esposito or he will be fired. Esposito is too kind-hearted to allow his (after all) friend to become unemployed because of him and agrees to go to prison to save Buttoni.

So, the motive of the crook(s) to help a police officer is different, in Italy it is empathy, in Israel business reasons.

אזולאי (Azulay) is not too happily married but still married. Consequently when a young, cute, pretty hooker (with the indispensable heart of gold) enters his life (he took pity on her and let her escape during a raid), their relationship cannot trespass the platonic stage, although she invites him to visit her whenever he wants. For free, of course! This prostitute, מימי (Mimi), played sweetly by ניצה שאול (Nitza Shaul) is the third in the line of sexy Israeli beauties featuring more or less prominently in films by קישון (Kishon).

קישון (Kishon) directed his penultimate film as the classical “invisible” director, without any modernist escapades, but he gave the actors a chance to show what they were able to do in front of the camera. A small shift in the muscles of a face can mean a lot. שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir), the leading actor, shows us a whole spectrum of emotional nuances in close-ups, but neither physical comedy is alien to him. No wonder he was an Israeli film star[8]!

Generally speaking, the films made by קישון (Kishon) are not of the kind where the whole room bursts into a never-ending ROFLMAOs. His humour is too subtle for that. Too warm. And this film is the warmest of them all. There is a lot of empathy in the telling of the story of this honest and naïve man. The best Israeli films all the way to the present day nurture this combination of tragedy with comedy that makes them so full of real life.

This is the only film made by קישון (Kishon) with an original screenplay, not as an adaptation of previous writings or characters.

The main objections to this film were again that קישון (Kishon), an Ashkenazi, mocks the Sephardim through the title character, but the actual truth is a little bit different. His pompous, but not more capable superior (probably already reached his level of incompetence), פקד לפקוביץ׳ (Captain Levkovich), is an Ashkenazi. However, as said above, in everyday situations (pacifying the orthodox Jews, interpreting for the French), אזולאי (Azulay) copes better than him.

The film was nominated for Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1965. The winner was Vittorio de Sica’s Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (The Garden of the Finzi-Contini), and the other nominees were どですかでん (Clickety-Clack) by 黒澤 明 (Kurosawa Akira), Jan Troell’s Utvandrarna (The Emigrants) and Чайковский (Tchaikovsky) by Игорь Васильевич Таланкин (Igor Vasilyevich Talankin).

The film won the 1972 Golden Globe award for Best Foreign Language Foreign Film. The other nominees were Éric Rohmer’s Le genou de Claire (Claire’s Knee), Bernardo Bertolucci’s Il conformista (The Conformist), Чайковский (Tchaikovsky) by Игорь Васильевич Таланкин (Igor Vasilyevich Talankin) and André Cayatte’s Mourir d’aimer / Morire d’amore (To Die of Love).

The film won several other awards, such as best foreign film in the Barcelona film festival and best director in the Monte Carlo festival. In Israel it is considered a cinematic classic.

So two more unseen movies remain to be mentioned.

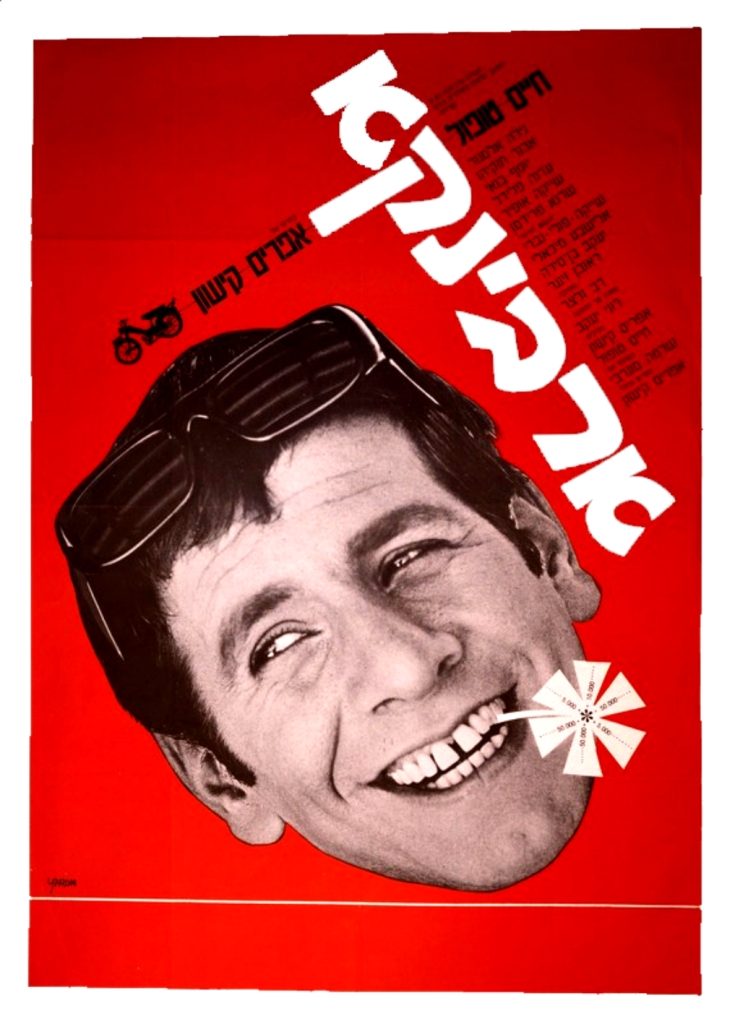

The second film made by קישון (Kishon) is the 1967 ארבינקא (Ervinka[9]). The titular character, a small con man played by חיים טופול (Chaim Topol), falls in love with רותי (Ruti), a police officer who does love him back[10], but is appalled by his way of life and concerned that he is on a slippery slope to a life of crime. ארבינקא (Ervinka) first appeared in short stories as a kind of the author’s alter ego. This is the first film by קישון (Kishon) in which שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir) plays a confused policeman, a role that will be expanded in the director’s next two films.

Of course, רותי (Ruti) played by גילה אלמגור (Gila Almagor) is the obligatory Israeli beauty in this film (again!).

The last film in the director’s opus was the 1978 השועל בלול התרנגולות (The Fox in the Chicken Coop), based on the author’s satirical book by the same name. אמיץ דולניקר (Amitz Dulniker), an aging member of Knesset, played by שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir)[11], is sent out of town for a holiday after he collapses during one of his endless, tiresome and meaningless tirades and ends up in a bucolic and carefree קיבוץ (kibbutz) in the middle of nowhere. Such an atmosphere is totally alien to him and he decides to bring some order in the villagers’ lives by organising a government. Do I have to stress that it eventually ends in a catastrophe? The film was unsuccessful both with the public and with the critics and, as the first significant failure of אפרים קישון (Ephraim Kishon) in Israel since he first appeared in public in 1952, dissuaded the director from continuing his film career. The main problem with the film might have been that the book was adapted 23 years after it was written with the political climate in Israel having changed a lot in the meantime.

So these are the films by אפרים קישון (Ephraim Kishon) that I have both seen and not seen.

[1] Was I imagining things, or was he really lisping… or more accurately, lishping while speaking? You know, [ʃ] instead of [s], [ʒ] instead of [z]…

[2] טופול (Topol) will become an international star with his role of Tevye the milkman in Norman Jewison’s 1971 film Fiddler on the Roof.

[3] איינשטיין (Einstein) invited הצ׳רצ׳ילים (The Churchills), a leading force in the early Israeli beat scene, to be his backing band on that LP. They played on half of the tracks on it. After that they gigged and recorded three more albums together.

[4] Its basic meaning is ‘homeland’, but in fact it is much much more than that, a feeling, a belonging, a seal of origin.

[5] In His book Almost the Whole Truth, about the inspiration behind his short stories, novels, plays and films, קישון (Kishon) mentions תעלת בלאומילך (The Blaumilch Canal) in passing:

The secret is called “Almost the whole…

Journalists write about what is interesting, writers write the truth and humorists write an almost the whole truth. What matters is that “almost the whole”.

When a slightly tipsy backup worker from the road construction sector pierces the sidewalk in front of our house with a pneumatic drill it is unbearable. But when he digs up the whole city and makes a Blaumilch canal in it, then it suddenly becomes ridiculous.

“Eureka!” exclaim serious humour researchers at this point. “Now we have a solution: we just need to start from reality and push things to the absurd.”

Eh, if it were that simple…

Last year, when I showed my passport to a police officer at the Belgrade airport, he kindly said:

“Yeah, Mr. Kishon from Israel!”

Suddenly a nice Yugoslav behind me got excited:

“Excusez,” he said, “have I heard that the gentleman is from Israel and that his name is Kishon?”

I answered in a sonorous voice:

“You heard right, sir.”

The gentleman was even more excited:

“Wouldn’t you perhaps be a relative of the writer Kishon?”

I retorted as Lohengrin did when declaring his divine origins in the third act:

“No, sir, I’m the writer Kishon in person.”

“Too bad,” said the nice gentleman, turning away disappointed and leaving.

Funny, isn’t it?

At least I like it very much. Unfortunately, that scene didn’t turn out that way. Namely, after his “Too bad” the gentleman continued “Please do not misunderstand me. I have read somewhere in the newspaper that one of your cousins is an Egyptologist like me…”

And that’s it. With Egypt, that scene isn’t even half as funny. The story only became comical when I left out the point.

Here, therefore, it was not necessary to “push things to the absurd” but the exact opposite.

(Retranslated by me.)

[6] He is somehow rather learned in the subjects of תורה (Torah) and תלמוד (Talmud) as well as Yiddish, which is funny since he is obviously a Sephardi Jew!

[7] However, the phrase is also the Italian name of the children game tag.

[8] Alas, as a heavy smoker, שייקה אופיר (Shaike Ophir) died from lung cancer in 1987 at the age of 59.

[9] A hypocoristic of Ervin, in the film it is actually pronounced Arbinka.”

[10] Does this setting not remind your of the love story between convenience store robber H.I. “Hi” McDunnough and police officer Edwina “Ed” in the Coen brothers’ 1987 film Raising Arizona?

[11] Their fourth film together!